Where Dead Men Lie is a fifteen-minute film from 1972 based on Henry Lawson’s 1897 short story “The Australian Cinematograph”. The film was made to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Lawson’s death, at Abbotsford in Sydney, on September 2, 1922, and features the voices of the actors Jack Thompson and Max Cullen.

In 1892, a Frenchman, Léon Bouly, had patented an invention which he called the cinématographe, a combination of two Greek words, kinemat (motion), and graphe (writing, drawing). He lacked funds to maintain the patent fees and sold his rights to the device and its name to the Lumière brothers. They applied it to their own device, a camera that could record and project film, in 1895.

This essay appeared in a recent Quadrant.

Subscribers had no need to wait for the paywall the come down

“The Australian Cinematograph” begins with the opening lines of Barcroft Boake’s 1891 poem “Where the Dead Men Lie”:

Out on the wastes of the Never Never—

That’s where the dead men lie!

There where the heat-waves dance forever—

That’s where the dead men lie!

The story is a reminiscence. The narrator, pipe in hand, is sitting on a school-house veranda, surveying a landscape in the South Island of New Zealand. It is a “softly beautiful green and gold September afternoon”, but after a gale on the previous night, and with the sea becalmed, “a poetical cynic might expect to find, on the black sand at the foot of the boulder margin, a drowned sailor”. Boake’s lines come to him:

Out where the grinning skulls bleach whitely,

Under the saltbush sparkling brightly—

Out where the wild dogs chorus nightly,

That’s where the dead men lie!

It must be the haunting music of the song; or because we are exiled and lonely here; or because I know the land that gave it birth (and killed the poet) … The sunset colours fade from along the snowy peaks of the Kaikouras; the scene blurs and darkens … Strong swelling music somewhere, with words of the song haunting it:

Out on—the wastes of—the Never Never

That’s where—

A great plain covered with greyish dust … a blind sun blazing in a brassy sky, and the heat visibly rushing across every object in dancing, dazzling waves … In the foreground a dry “tank”, or clay-pan, from which the last pint of water has evaporated but an hour or so … And all around the skeletons—bleached bones and blackened hides and scraps of hide—of stock that perished … And, away to the right of the clay-heap, between it and the dazzling horizon, three black figures—three horses and two riders.

In a film, an establishing shot at the beginning provides a wide perspective on that part of the world which the characters inhabit. Sometimes, a voice off-camera will be used to provide information about the action to come, and to add to the atmosphere which the film-maker is trying to convey. From there, the shots become closer and tighter on groups, individuals and faces.

Among the group making their way through the drought-stricken country of the Never Never is an overland drover. On the home track, he has taken his chances across the dry stretch once too often, and knows:

he is doomed. No gesture of despair save a quick straightening of his right arm by his side, but the free hand closes and tightens for a moment … The drover lifts his hands, and shading his eyes, looks out over the plain—over our heads as it were—but he sees nothing.

In cinematic parlance, Lawson has given a detailed “treatment” of the film he is envisaging with his imaginary camera-eye. There is no dialogue, and he gives much attention to the actions and gestures of the ill-starred drover and his companions.

And the scene blacks out—a blackness as on a cinematic screen where the focus is shut off … and through it all, the words of Barcroft Boake’s song, now wailing, now fiercely triumphant.

A scene-change, and we see the veranda of a cottage on a selection where the drover’s wife sits with their baby, awaiting his return. One of their other children, a bare-legged boy, keeps a look-out from his vantage point on a slip-rail in the cow-yard, “and traces the track to the river through the gathering dusk”. The final sentence: “The scene fades, leaving the boy against the sky to the last, watching for father.”

Another scene-change, and the camera-eye pans once more over the great plain, no longer the cruel hell in which the overlander has perished, but transformed by rain into an Australian landscape befitting Paterson’s “vision splendid of the sunlit plains extended”:

Three drovers ride on to the scene from the right and dismount. One of them is the brother of the missing man. It is he who discovers the body. A pocket-book is found among the dead man’s effects with a last message to “my poor wife”.

The brother is consoled by his mate. “The scene fades rapidly.”

Lawson writes in the final section of the story: “The last scene is also a ‘speaking’ as well as a ‘living’ picture to me, and a brighter one in spite of all, for the drover’s wife is quiet now and sits tearful but resigned.” She has been given a false account of her husband’s death to soften the blow. She is told by his brother’s mate, “Andy”, that her husband “died of heart disease at the head-station … scarcely felt any pain, and his last words were for her not to fret”. “Andy” never once takes his solemn grey eyes from those of the drover’s wife, lest she might, by a mere chance, doubt him. And with that close-up, the story concludes. The narrator has no name in the story: whether he is “Andy” is not spelt out; the inverted commas give the clue.

That Lawson set great store by the power of the visual image, and understood the potential of the moving visual image, there can be no doubt. In his 1899 essay “If I Could Paint” he wrote:

A picture has a greater hold and a more lasting impression on the mind of the people than printed words, especially in these days, when picture printing has been brought to such perfection and copies of a great painting can be scattered broad-cast. A painting is dumb, but type is dumber as far as speaking to the heart of the people is concerned.

The rest of the essay is, in effect, a catalogue of an imaginary collection of paintings about Australia for which he has chosen the subject matter.

Lawson’s fictional catalogue includes pictures that are character studies of Australian “types”, in the William Hogarth tradition. He presents a host of promising subjects taken from bush and city life: as well as the drover, the cocky and the digger, there is the furtive ne’er-do-well in the slum alley; the Saturday afternoon inebriate; the young female teacher grimly toughing it out in a bush schoolhouse; “Paddy’s Market on a Saturday night—a world of types, humour, pathos, and tragedy there”. For landscape subjects, he suggests “unknown places” like McDonald’s Hole at Mudgee and the Capertee Valley.

CINEMATIC instincts are also revealed in the particular emphasis Lawson places on sound in some of his stories. Song lyrics are integral to these stories, and they are not mere quotations by the narrator, but are actually being sung by people in the story. They are songs with which many of the readers of his day would have been familiar. By appealing to the reader’s aural imagination, Lawson provides a musical score which creates an atmosphere and draws the threads of the story together.

In the opening section of “The Songs they Used to Sing” (1899) the unnamed narrator, who we can assume is speaking for Lawson, assembles what is virtually a soundtrack album. It comprises songs he recalls being sung, twenty years or more before, in the evenings on “the diggings of Lambing Flat, the Pipeclays, Gulgong, Home Rule and so on through the roaring list; in bark huts, tents, public houses, sly-grog shanties”.

The narrator has a memory, from his boyhood on the diggings, of a girl’s voice coming from another hut in the darkness, singing of the bonnie hills of Scotland. He can remember songs from America being sung: “The Prairie Flower”; a temperance song from 1864, “Father, Dear Father, Come Home with Me Now”, “a sacred song, then, not a peg for vulgar parodie”; “Blue Tail Fly”, better known to us as “Jimmy Crack Corn”; and “Madeline”.

The next section of the story opens with a specific location on a Saturday night: “The great bark kitchen of Granny Mathews’ Redclay Inn. A fresh back-log thrown behind the fire, which lights the room fitfully. Company settled down to pipes, subdued yarning, and reverie.”

We are then treated to a concert, a filmed concert in effect, in which we are able to enjoy the responses of those assembled who constitute the audience:

Flash Jack volunteers, without invitation, preparation, or warning, and through his nose:

Hoh!—There was a wild kerlonial youth,

John Dowlin was his name! …

Then, by popular request, Abe Mathews, “bearded and grizzled”, gets up and sings “The Golden Vanitee”.

Toe and heel and flat of foot begin to stamp the clay floor … Heels drumming on gin-cases and stools; hands, knuckles, pipe-bowls and pannikins keeping time on the table.

And we sunk him in the Low Lands, Low!

The Low Lands! The Low Lands!

And we sunk him in the Low Lands, Low!

Up steps Little Jimmy Nowlett, Cockney bullock-driver, with a costermonger’s song from the 1820s, “All Around My Hat”: “Hall!—Round!—Me—Hat! / I wore a weepin’ willer!” A Cockney costermonger has vowed to be true to his fiancée, sentenced to seven years’ transportation in Australia for theft, and to mourn her absence by wearing green willow sprigs in his hatband for “a twelve-month and a day”.

Old Poynter, Ballarat digger, known as “Pinter”, sings of “Covent Gar-ar-a-r-dings” and of Jessie who loves a sailor bold. “Hong-kore, Pinter! Give us the ‘Golden Glove’!” cries the crowd.

From a camp across the gully can be heard echoes of “The Old Bark Hut”, “The Old Bullock Dray”, “Rule Britannia!” and “Yanky Doodle … All the camps seem to be singing tonight.” And then come the opening words of a song which sounds familiar, but not identical, to lyrics well-known to Australians. “Good lines, the introduction,” the narrator observes:

High on the belfry the old sexton stands,

Grasping the rope with his thin, bony hands!

The opening words of “Click Go the Shears”, dating from the early 1890s, are easily substituted in the reader’s mind for the lyrics of the American Civil War song “Ring the Bell, Watchman!”

Out on the board the old shearer stands,

Grasping his shears in his long, bony hands.

Granny Mathews coaxes her shy niece into singing the 1864 American gospel song “Shall We Gather at the River?” and the mood has changed in the Redclay Inn: the men “who have them on instinctively take their hats off”.

Shall we gather at the river,

Where bright angels’ feet have trod?

The beautiful, the beautiful river

That flows by the throne of God!

In the early hours of the morning, Italian workers go past from their last shift on the claim, singing a litany in the frosty moonlight. “Hands are clasped across the kitchen table,” and the concert concludes with one Peter McKenzie leading the company in “Auld Lang Syne”—“And hearts echo from far back in the past and across wide, wide seas … The kitchen grows dimmer, and the forms of the digger singers seemed suddenly vague and insubstantial, fading back rapidly through a misty veil.”

Lawson carried the leitmotif of the song “Shall We Gather at the River?” into another story published in 1901. The story “Shall We Gather at the River?” introduces the character of Peter McLaughlin, apostle of the outback, preacher and remittance man. It opens with a quotation from Lawson’s poem “The Christ of the ‘Never’” (1900):

God’s preacher, of churches unheeded,

God’s vineyard, though barren the sod.

Plain spokesman where spokesman is needed,

Rough link ’twixt the Bushman and God.

In the midst of a fearful drought, and on a blazing hot Sunday, the local parson fails to arrive for a service in the wretched old hut that serves as a school, so Peter takes on the task. He “didn’t preach much of hope in this world. How could he?” The rivers in the district are dried up, dead animal carcasses lie on the baked creek beds. But he speaks of the support the locals have given each other in hard times past, and at the end of his sermon, accompanied by a Miss Southwick on a portable harmonium, he begins to sing the hymn about “the beautiful river that flows by the throne of God”. By the power of his sympathy, he takes the congregation with him; abandoning small local animosities, they join him in the song and leave the hut with a renewed sense of community and purpose.

In another McLaughlin tale, “The Story of Gentleman-Once” (1901), he is yarning by a campfire after tea “in a bend of Eurunderee Creek … in the broad moonlight”, with mates Joe Wilson and Jack Barnes, “shearers for the present”, and a swagman, Jack Mitchell. Again, music is an integral part of the story: “Up the creek on the other side was a surveyors’ camp, and from there now and again came the sound of a good voice singing verses of old songs; and later on the sound of a violin and a cornet being played, sometimes together and sometimes each on its own.”

As the three men are talking and reflecting, the voice from the surveyor’s camp strikes up a song set to the words of a famous poem by the Englishman Thomas Hood: “I remember, I remember, the house where I was born.” “The breeze from the west strengthened and the voice was blown away. ‘That chap seems a bit sentimental but he’s got a good voice,’ said Mitchell.” Peter takes up the theme of remembering invoked by the song lyrics: “By the way, Mitchell, I forgot to ask after your old folk … I remember your father well, Jack.” The wind falls again, and the singer can be heard again singing, “I remember, I remember”, and Peter asks Joe Wilson how his mother is faring in Sydney.

The story turns to a tale of personal reminiscence: “‘I remember,’ said Peter quietly, ‘I remember a young fellow at home in the old country.’” Peter does not identify himself; he speaks of the young man in the third person. He says that young man would “give the world” to be able to clasp his father’s hand or spend another year with his mother. “It has been too late for more than twenty years.”

The surveyor with the good voice starts to sing again, this time “Bonny Mary of Argyle”: “I have heard the maven singing …” The breeze has changed and strengthened and the violin can be heard playing “Annie Laurie”. “They must be having a Scotch night in the camp tonight,” says Mitchell.

The voice takes up “Annie Laurie”: “Maxwelton braes are bonny”. “Mitchell threw out his arm impatiently. ‘I wish they wouldn’t play those old songs,’ he said. ‘They make you think of damned old things. I beg your pardon, Peter.’” Such is the respect people have for Peter, tolerant and uncensorious as he is, that they curb their language in his presence. And such is the power of the music that sadness has now pervaded the group. “It is in the hearts of exiles in new lands that the old songs are felt.”

The cornet starts up in the surveyors’ camp, playing Robbie Burns’s “Ye Banks and Braes”. “‘Their blooming tunes seem to fit in just as if they knew what we were talking about,’ remarked Mitchell.” Lawson supplies some of the lyrics, as if the singer has joined in:

You’ll break my heart, you little bird,

That sings upon the flowery thorn—

Thou mind’st me of departed joys,

Departed never to return.

“‘Damn it all,’ remarked Mitchell, ‘I’m getting sentimental.’” Peter returns to the theme of “I remember”, and tells the tale of a remittance man, one of “a big clan” in the bush, the clan of “Gentleman-Once”. Though he does not say so, it can only be his own story. The music from the surveyor’s camp which produced the mood of reverie has changed by the time Peter concludes his story and the men finish up for the night: “The cornet up the creek was playing a march.”

In The Legend of the Nineties, Vance Palmer wrote of Henry Lawson: “As a writer he preferred the concrete image to the vague abstraction, the use of the imagination on what was near at hand rather than what was remote.”

In cinematic terms, Lawson provides the prop master and set designers of a film crew with a head start. He wrote list stories, in which he provides a record of a character’s worldly goods. The cumulative effect of this wealth of detail is to reinforce the poverty in which his characters are living.

In “The Romance of the Swag” (1901), Lawson’s minute description of the components of a typical swag is followed by an image rich in pathos:

Some old sundowners have a mania for gathering, from selectors’ and shearers’ huts, dust heaps etc., heart-breaking loads of rubbish which can never be of any possible use to them or anyone else. Here is an inventory of the contents of the swag of an old tramp who was found dead on the track, lying on his face on the sand, with his swag on top of him, and his arms stretched straight out as if he were embracing the Mother Earth, or had made, with his last movement, the Sign of the Cross to the blazing heavens: Rotten old tent in rags. Filthy blue blanket … leaky billy-can … fishing-line … mutilated English dictionary … a Shakespeare, book in French and book in German, and a book on etiquette and courtship.

A feature of Lawson’s art is his ability to write natural dialogue, minimalist but brimming with laconic humour. In “Mitchell: A Character Sketch” (1893), the itinerant Jack Mitchell calls in at “a mean station” and approaches the manager for work. The rhythms of the exchanges between the two men read like those in a script:

“Good day,” said Mitchell.

“Good day,” said the manager.

“It’s hot,” said Mitchell.

“Yes, it’s hot.”

“I don’t suppose,” said Mitchell; “I don’t suppose it’s any use asking you for a job?”

“Naw.”

“Well, I won’t ask you,” said Mitchell, “but I don’t suppose you want any fencing done?”

“Naw.”

“Nor boundary-riding?”

“Naw.”

“You ain’t likely to want a man to knock round?”

“Naw.”

“I thought not. Things are pretty bad just now.”

“Na—yes—they are.”

“Ah, well; there’s a lot to be said on the squatter’s side as well as the men’s. I suppose I can get a bit of rations?”

“Ye-yes.” (Shortly) “Wot d’yer want?”

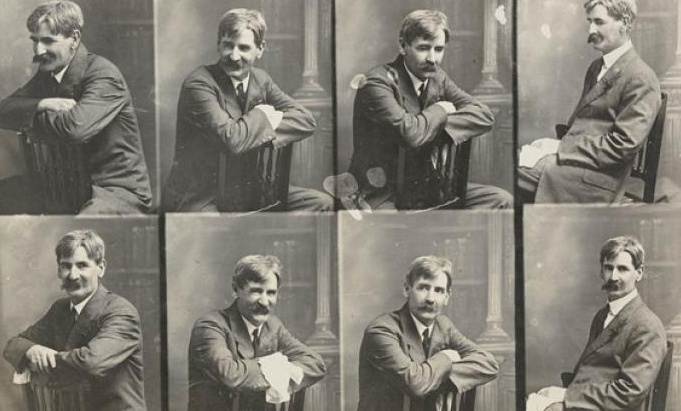

This year marks the centenary of Henry Lawson’s death on September 2, 1922. A finalist in the biennial sixty-seventh Blake Prize 2022 has painted a diptych with the title A Foreign Father, and a Child in the Dark. The title is a reference to Lawson’s story “A Child in the Dark, and a Foreign Father” (1902), though the painting is not a depiction of the story itself.

Lawson’s tale contains echoes of his own childhood: his father, Niels (known as Peter), was a Norwegian sailor who, on arrival in Melbourne, left his ship to join the gold rush. The story takes place on a hot New Year’s Eve during a drought. Nils, the father, returns home, on foot and in the dark, from a day’s work in a farming town about five miles away. The bush hut is unlit; his family has gone to bed. He speaks reassuringly to his elder son, who has been feeling ill. Lawson describes the meagre, untidy interior with fastidious precision.

Two months after Henry Lawson’s death, an essay about him by A.G. Stephens appeared in Art in Australia. Stephens wrote:

He leaves us a gallery of literary pictures of Australian persons and scenes. Past melancholy and bitterness … he leaves us a rich harvest of shrewd and chuckling humour with its correlative sense of pathos, a generous sympathy with the downtrodden and the distressed, a passionate love of Australia the nation, a noble enthusiasm for the humanity he understood.

Diana Figgis lives in Sydney. She has written articles for Quadrant on “Waltzing Matilda” and John Shaw Neilson, among other topics

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search