Nature repairs her ravages—but not all. The uptorn trees are not rooted again; the parted hills are left scarred: if there is a new growth, the trees are not the same as the old, and the hills underneath their green vesture bear the marks of the past rending. To the eyes that have dwelt on the past, there is no thorough repair. —George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss (1860)

Few now recall the name of Thomas William Bowlby, solicitor and special correspondent for the Times, but in the autumn of 1860 his whereabouts were a matter of truly international concern. Bowlby had been engaged by the Times to report on the conduct of the Second Anglo-Chinese War, now more emotively known as the Second Opium War, and over the course of the summer he had painstakingly documented, as he put it, the “ocular demonstration of the irresistible might of England and France” that was then being furnished to the Great Qing.

This essay appears in December’s Quadrant.

Click here to subscribe

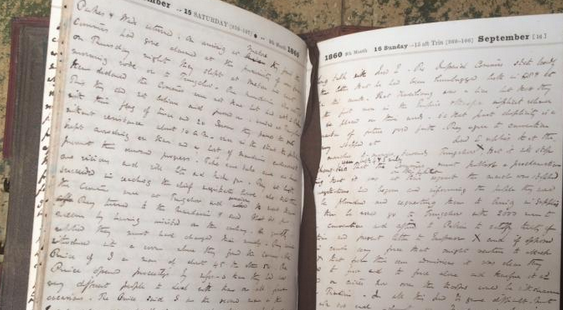

While his official dispatches thrilled audiences back home, his private diary—rediscovered in 2015 in a home in Carlton Scroop, Lincolnshire, stuffed inside an Ottoman box, and auctioned by Hansons on July 31, 2019, for £10,000—has proven an even better source of information about the campaign. In his trusty leather-bound, brass-clasped Letts of London journal (below), the war correspondent described in far more personal terms the “fearful amount of violence” and “regular organised looting” he witnessed on both sides, as well as more pleasant sights, like the monasteries “excellently built of brick, the roofs and gables ornamented with fantastically carved figures in stone, very like the Gothic”, and above all the gardens with “roses, carnations, pinks, and hollyhocks in abundance; and there are pears, plums, apricots, peaches, nectarines, wild grapes, etc., fortunately not ripe or diarrhoea would be prevalent”.

A seasoned war correspondent, Bowlby knew that the conflict would be vicious and without quarter; his entry for July 8, 1860, tells us that the Chinese “do not intend to yield”, as evidenced by “the petitions and memorials of Sang-ko-lin-sin [the Mongol general Sengge Rinchen] which breathe iron and blood, destruction of barbarians and, above all, no entry to Pekin”. Soon thereafter Bowlby experienced something like a presentiment:

During the past three evenings, between seven and nine, we have seen a large comet to the West said not to be marked in the nautical almanack. When I was in the Dolmschen in ’58 two large comets were visible. The peasants asked us when the war was going to begin, as the Crimean campaign was preceded by a comet in ’54. We laughed, but soon afterwards the great war broke out between France and Austria in Italy. And here is another comet, with another war on hand.

A Chinese observer of that comet would have considered it a disturbing astrological omen, a “vile star”, and a certain harbinger of heaven-sent calamity.

It did not, as it happened, take long for the allied forces to storm the Taku Forts, capture the ports of Yantai and Dalian, and open the way towards the Qing capital. With the war seemingly winding down, Bowlby made the understandable, though ultimately fateful, decision to accompany the British envoys Henry Loch and Harry Smith Parkes during their mission to parley with Qing officials in Tungchow.

The Anglo-French delegation arrived at Tungchow under a flag of truce on September 14, 1860, and there the British commissioners encountered an elderly Mandarin who wondered aloud whether peace was truly in the offing. When they replied in the affirmative, the Qing bureaucrat expressed relief: “So much the better, we can now go home, we are all tired of staying here.” Nearby another Mandarin was hard at work in his garden, spade in hand. In Bowlby’s telling, “astonished at the sight they rode up and asked what he was doing. To this he replied ‘digging in the garden’. He was burying his sword and cap.” Few doubted that the war was effectively over.

Bowlby’s diary entry for September 16—the last he ever made—was all business. “Demand million taels down at Pekin. For remainder takes 40 per cent. gross receipts import duties, equal to 50 per cent. net.”

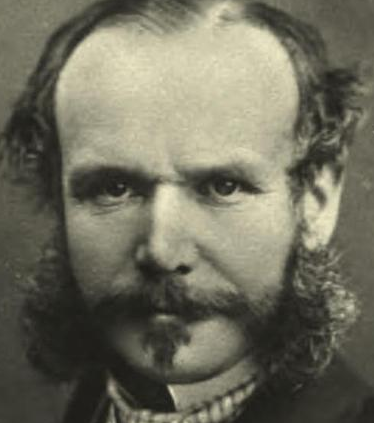

But after four days of talks it became clear that something was deeply amiss. Yizhu, the Xianfeng emperor, had been utterly humiliated by the results of the war thus far, and his military advisers were urging a last stand at Peking. “Will you cast away the inheritance of your ancestors like a damaged shoe? What would history say of your Majesty  for a thousand generations to come?” Tsao Tang-yung, the ex-Censor of the Hoo-kwang Provinces, demanded to know. So the Qing general Sengge Rinchen was authorised to take action in equal parts decisive, foolhardy and demented, and as a consequence the Anglo-French envoys, their escorts, and the journalist Bowlby were ambushed, seized and trussed up like lowly rebels. Loch, Parkes and their Sikh orderly were taken to the Peking Board of Punishments, where they were imprisoned in a ward with some sixty felons of the first class. The rest of the company, including Bowlby (at right), were marched to the Old Summer Palace of Yuanmingyuan, where their suffering would begin in earnest. It would be iron and blood and the destruction of barbarians after all.

for a thousand generations to come?” Tsao Tang-yung, the ex-Censor of the Hoo-kwang Provinces, demanded to know. So the Qing general Sengge Rinchen was authorised to take action in equal parts decisive, foolhardy and demented, and as a consequence the Anglo-French envoys, their escorts, and the journalist Bowlby were ambushed, seized and trussed up like lowly rebels. Loch, Parkes and their Sikh orderly were taken to the Peking Board of Punishments, where they were imprisoned in a ward with some sixty felons of the first class. The rest of the company, including Bowlby (at right), were marched to the Old Summer Palace of Yuanmingyuan, where their suffering would begin in earnest. It would be iron and blood and the destruction of barbarians after all.

Wet ligatures were applied to the prisoners’ limbs, and the cords gradually tightened as they dried; the pressure was so immense that hands were soon “swollen to three times their proper size, and as black as ink”, as Bughel Sing, one of the few captives to survive the experience, later testified. Dirt was crammed down the thirsty prisoners’ throats, food was withheld almost entirely, beatings were regularly administered, and lingchi, or slow slicing, the infamous “death by a thousand cuts”, was even employed. Thomas William Bowlby withstood five days of this inhumane treatment before expiring. Two of the prisoners—Captain Brabazon of the Royal Artillery and the French Abbé de Luc—were meanwhile taken to the parapet of the bridge at Pah-li-chiao, where they were beheaded and hurled into a ditch. It was not until October 8 that Loch, Parkes and six other members of the delegation were released. A mere ten minutes after they departed, a message arrived from the Xianfeng emperor ordering that the envoys were to join in the fate of the thirteen souls that had already perished at the hands of Sengge Rinchen.

Peace negotiations had obviously foundered, and the Anglo-French expedition was obliged to continue its advance towards Peking. The expeditionary force achieved a stunning victory at Eight-Miles Bridge on September 21, 1860, opening the route to the Old Summer Palace, where a search was made for the missing persons. It was clearly a recovery, and not a rescue, operation. Maltreatment and quicklime had rendered many of the corpses unrecognisable, but Bowlby’s remains could be identified owing to a “peculiar formation of his head and brow and … a peculiarity in one of his feet”. On October 17, what was left of Bowlby, as well as the mangled bodies of Lieutenant Anderson and the attaché William de Norman, were taken to the Russian cemetery just outside the Anding Gate, the “Gate of Stability”, and buried with great solemnity. Months later, a search would be made of the dike below the Pah-li-chiao bridge, and bones were unearthed, together with a telltale scrap of striped cloth, that of an artillery officer’s trousers, and a piece of silk that belonged to ecclesiastical attire. No skulls were found.

The day after Bowlby’s interment, the expedition commander Lord Elgin (a close personal friend of the slain journalist) settled on the form that his vengeance would take: the Yuanmingyuan, the “Gardens of Perfect Brightness”, the “Garden of Gardens” that graced the site of the Old Summer Palace (pictured above)—and also the site of Anglo-French captives’ calvary—was to be laid to waste over the course of two days of pillaging. Afterwards, a sign would be erected on the smouldering wreckage, bearing characters reading: “This is the reward for perfidy and cruelty.” The sack of the garden complex was meant to serve as an exemplary lesson, for as Erik Ringmar later put it, “to flatten the Yuanmingyuan seemed appropriate since the action would hurt the emperor personally rather than his subjects”. Elgin’s plan worked, at least in the short term; the Xianfeng emperor vomited blood when he heard of the devastation, and was dead within a year. The editors of the Times were, for their part, fundamentally satisfied with the reprisal:

the three victims, Bowlby, de Norman and Anderson, lie together in the Russian Cemetery, where they have been buried with honours that may have impressed even their Chinese murderers with the importance which the English attach to the lives of their countrymen, and their graves may serve to record the crime of which the blackened ruins of the Summer Palace of the Emperor will long record the punishment. If, as we hope, such punishment has been inflicted as the evidence of guilt would justify, we must be content to mourn, and be silent.

Posterity, on the other hand, would take no part in that vow of silence.

Some participants, like Charles George “Chinese” Gordon and the chaplain Robert McGhee, later described their conflicted feelings about the damage that had been done. Gordon said he could

scarcely imagine the beauty and magnificence of the places we burnt. It made one’s heart sore to burn them; in fact, these places were so large, and we were so pressed for time, that we could not plunder them carefully. Quantities of gold ornaments were burnt, considered as brass. It was wretchedly demoralising work for an army … It was a scene of utter destruction which passes my description.

For McGhee, “it was a sacrifice of all that was most ancient and most beautiful”, and “whenever I think of beauty and taste, of skill and antiquity, while I live, I shall see before my mind’s eye some scene from those grounds, those palaces”. Other contemporaries were harsher still. Victor Hugo, a year later, lamented the loss of that “inexpressible construction, something like a lunar building”, and expressed nothing but horror that the “French empire has pocketed half of this victory, and today with a kind of proprietorial naivety it displays the splendid bric-a-brac of the Summer Palace. I hope that a day will come when France, delivered and cleansed, will return this booty to despoiled China.” (By way of thanks, a bust of Hugo now graces the grounds of the palace.)

All that remains of the Summer Palace.

The German academic W.G. Sebald, in his 1995 novel Die Ringe des Saturn, described the palace gardens as an Arcadia where “the whole incomprehensible glory of Nature and of the wonders placed in it by the hand of man was reflected in the dark, unruffled waters”, and surmised that the

true reason why Yuan Ming Yuan was laid waste may well have been that this earthly paradise—which immediately annihilated any notion of the Chinese as an inferior and uncivilized race—was an irresistible provocation in the eyes of soldiers who, a world away from their homeland, knew nothing but the rule of force, privation, and the abnegation of their own desires.

It is possible that Elgin and his men were driven by subconscious motivations apart from a combined lust for revenge and lucre when they tore through the gardens on October 18 and 19, 1860. What is undeniable, in any event, is that Elgin’s actions made a far deeper impression than would have been achieved by, say, the sacking of Qing wharves, warehouses or bulwarks.

The burnt and plundered remains of the Old Summer Palace would in time be seen as China’s official “national wound” and an eternal emblem of the bainian guochi, or “Century of Humiliation” that lasted from the Opium Wars to the end of the Chinese Civil War. It is this sense of humiliation—which likewise informs China’s hardline policies towards the Tibetans, Uighurs, Hong Kongers, and other groups perceived as threatening Zhongguo’s hard-won national cohesion—that gives the gardens their everlasting significance. To this day, the Yuanmingyuan has been lovingly preserved in a state of total disarray, not unlike the eerie French village of Ourador-sur-Glane, destroyed by the Nazis in 1944, or the unrestored Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, with its skeletal, half-shattered Genbaku Dome. Replacing Lord Elgin’s proclamation is one entreating the visitor to “never forget the humiliation of the nation”, a message that has definitely been received.

The Yuanmingyuan is now afforded positively talismanic properties in the Chinese public square. When the People’s Liberation Army Daily reported on the 1997 handover of Hong Kong, it solemnly proclaimed that China had “finally removed the stain from the imperialists’ burning of Yuanmingyuan”. A decade later, when China was on the receiving end of French criticism for various human rights offences, the People’s Daily fired back: “If France wants to talk to China about human rights, they first need to apologise for what they did to Yuanmingyuan, and then return the great quantity of Chinese relics they stole”. In the “scorched ruins”, another Chinese journalist added, “I see a pool of blood.” A curator at the Chinese Poly Museum, when asked in 2018 about the palace’s sculpted zodiac heads, some of which have been recovered from abroad, and others of which remain missing, responded that “their return is the deepest hope of the Chinese people. It’s very sad and hard history for us. When the heads come back, we will finally feel the power of our country.”

What survives of the Garden of Gardens has become both a static lieu de mémoire and an active locus of cultural memory. Visitors might choose to attend an exhibition like the haunting 2010 photography showcase “Disturbed Dreams in the Ruins of the Garden”, or alternatively might prefer to take in the Beijing Dragon in the Sky Puppet Troupe’s boisterous (if slightly anachronistic) shadow play recreations of the events of 1860, replete with Chinese villagers bravely fending off curly-haired barbarians, accompanied by the shouts of “Kill the foreign devils!” Thus the Yuanmingyuan has been transformed, as Haiyan Lee articulated it, into something suspended between a “nationalist propaganda tool that distorts history and manipulates memory to promote a patriotism that borders on xenophobia” and “a Chinese Disneyland that sacrifices authenticity and good taste to profit and mass amusement”. Whether such a site, regardless of its grim history, truly deserves to be given “a meaning for Chinese akin to that of the Holocaust for Jews”, as Norman Kutcher would have it, is debatable. (One would imagine that the Memorial Hall of the Victims in Nanjing Massacre would be a more fitting focus for such sentiments, at the very least.)

So central is the Yuanmingyuan to the grievances that stem from the “Century of Humiliation” that the temptation exists to engage in the sort of mass psychoanalysis that W.G. Sebald attempted in attributing the sack of the gardens to deep-seated Western jealousy of Chinese cultural achievements. Is it possible that the ruins of the Yuanmingyuan are still seen as imbrued with the blood of the slaughtered Anglo-French captives, as well as the decadence, cruelty and sheer folly of the Qing dynasty? Does the preservation of the site by subsequent Chinese generations arise out of some admixture of guilt, shame and a need to maintain an imperial memento mori? Does the fact that the grounds were designed in no small part by the Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione, only to be wrecked by Western soldiers, somehow speak to the inadvisability of oriental-occidental syncretism? In their heyday, the imperial gardens were sublime in their vastness and variety; their ruins seem to have given rise to an equivalent array of sentiments, be they positive, negative or equivocal.

In 1796, the French armchair archaeologist Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy posited that ruins served as “a great book whose pages have been destroyed or ripped out by time, it being left to modern research to fill in the blanks, to bridge the gaps”. There are a great many blanks and gaps to fill in when considering the history of Yuanmingyuan, particular given that Lord Elgin’s assault on the Gardens of Perfect Brightness was in fact only the beginning of the site’s problems. The fire that swept through the palace grounds in 1860, the conflagration or “huojie”, was destructive enough, but it would be followed by three more “calamities”: of wood (“mujie”), of stone (“shijie”) and of soil (“tujie”). Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the imperial household began to fell the garden’s remaining trees, a process that accelerated during the Boxer Uprising. The Republican era would feature widespread spoliation of the remaining marble and tiles, mostly destined for the Peking mansions of warlords and the urban gentry. Under Mao Zedong, farmers and “sent-down” professors were put to work on the grounds in an effort to transform the ancient garden into productive tillage while, according to Wang Daocheng, “800 metres of the garden wall was once knocked down, 1000 trees were cut down and numerous stones were carried away by dozens of trucks during that period.” Worse still, as Vera Schwarcz has pointed out, “some remnants of the Summer Palace were literally slashed with knives by Red Guards”. Treating the remains of the park merely as Lord Elgin’s “humiliation ground” does not tell anywhere near the entire story.

We must remember that Chairman Mao had a particular distaste for pleasure gardens, one matched only by his loathing for sparrows (the Kill Sparrows Campaign of 1958 to 1960). “In all of its complex variety,” he observed in a 1938 speech at the Lu Xun Arts Academy, “the whole of China is like the Prospect Garden.” This was not, however, a good thing. Mao preferred “a blank sheet of paper free from any mark”, and gardens are quite the opposite. Indeed imperial Chinese gardens were, as Edward Schafer observed in his magisterial The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics, “in effect magical diagrams, vegetable cantrips binding the several natural realms of the whole world under the spiritual sway of the Son of Heaven”. Each floral species was laden with signification, with the lotus inseparable from Buddhism, the chrysanthemum a symbol of duration, the peony serving as the “queen of flowers”, the magnolia so prized that only emperors could cultivate them, and so on. The hortus gardinus thus represented a subtle but persistent reminder of the “Four Olds” (habits, ideas, customs and culture) that Mao so desperately and maliciously sought to eradicate.

The Great Leap Forward would become known as a time when “flower pots were broken and vegetables planted”, though famine took hold just the same, and tens of millions of peasants starved to death. Under Mao the Yuanmingyuan was subjected to the “calamity of soil”, and the Garden of Abundant Nourishment and other such marvels were dug up as well. Deng Xiaoping’s daughter Deng Rong recalled that “flowers and suchlike were regarded as reeking of petit-bourgeois sentimentality”. The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution that followed would do even greater damage, as the effort to root out feudalism, capitalism and revisionism led to what Maurice Meisner called a “strange negative utopianism”. Murals, statues, archways, gates and parks throughout Beijing and China as a whole were systematically demolished, though the “common mind”, as Hung Wu later wrote, “could hardly understand the reason for this massive destruction: the land freed from these ancient buildings seemed incommensurate with the energy and manpower wasted in the project”. Of course, the destruction was the end as well as the means.

It is something of a historic irony that the demolition and defoliation practised by the Anglo-French expedition were perfected a hundred years later under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party. One is hardly surprised, then, to find that there now exists a deeply ingrained fatalism in China when it comes to tangible cultural patrimony. The Chinese rarely speak of the “protection of historic sites and monuments” as Western heritage organisations might, but rather wenhua fengmao baohu, or the “protection of cultural aspects”. There is little confidence in the perpetual survival of the physical, as opposed to moral or spiritual, vestiges of the past. It cannot be denied that, as Zhuoliu Wu explained in his 1945 novel Orphan of Asia, “the intellectuals of the past, no matter what the period, were always left behind by the passage of time as they helplessly flailed around. Perhaps they were no more than rootless floating weeds in the current.”

The torrents of Chinese history, both literal and metaphorical, have provided the basis for Simon Leys’s oft-cited discussion of China’s “présence spirituelle et absence physique du passé”, wherein he observed:

Chinese architecture is typically made from perishable materials, and so possesses a sort of “built-in obsolescence”, degrading rapidly and requiring frequent reconstruction. This technical recognition produces a philosophical conclusion: in effect, the Chinese have transferred the problem—eternity does not dwell in the architecture, but rather in the architect.

Or, as the Sinologist Victor Segalen stated it in his 1912 poem “To the Ten Thousand Years”, “nothing stationary escapes the hungry teeth of time. Solid things are not fated to last. The immutable dwells not within your walls, but in you, the slow men, the continuous men.”

And in China, the exemplars of the slow and continuous men and women have always been the gardeners. When the Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai embarked upon a seemingly quixotic search for aspects of traditional Chinese culture that “can in a material sense be annihilated but in … essence never, and because of that may be brought to life again and again”, as documented in his brilliant 2004 travelogue Destruction and Sorrow Beneath the Heavens, he pursued his quarry into the Humble Administrator’s Garden (Zhuozheng Yuan) in Suzhou. “One of these indestructible forms could be the Chinese garden,” Krasznahorkai concluded:

because here, the Chinese garden, as an articulation of the classical spirit in an exquisite form, in a given garden, or a neighbouring garden, can nonetheless be destroyed, but the Garden in its own spirit remains—since neither can all the plants be expunged from the earth, nor the stones be made to vanish for all time, nor the plans of the pavilions and their depictions, nor all the books that describe the rules of their construction, those can’t be burnt or pulped or otherwise made unreadable—so that, if today, someone faithfully follows the prescriptions of tradition, then in every case the original may be rebuilt.

There is some comfort to be found, then, in the ongoing campaign to renovate the age-old gardens surrounding Nanjing’s Taiping Heavenly Kingdom Museum, where visitors are told that “the historical and literary views of the splendours of the Ming and Qing have been seen again at Reverence Garden”. Tobie Meyer-Fong has written of the refurbished Reverence Garden:

this vision of refined elites, emperors, and princes elides the once-useful revolutionary past of feminist, land-redistributing, anti-Manchu rebels—and similarly occludes a history of destruction and renovation in favour of sumptuous, timeless and eminently consumable images of wealth, power and leisure. The party and the government occupy the roles of emperor and elites as patrons and preservers of the garden.

Here we are a long way from the wilful breaking of flower pots and the trashing of imperial gardens.

That this is something of a trend may be seen in the Yuanmingyuan’s Repair 1860 project, launched on May 10, 2019, which entails the restoration of some 100,000 fragments of porcelain that have been unearthed from the grounds of the old Gardens of Perfect Brightness. Even better, in 2017 eleven lotus seeds were discovered during the archaeological investigation of one of the Yuanmingyuan’s ponds. Though dormant for more than a century, six of the seeds managed to sprout, and in April 2019 four of the ancient lotuses were transplanted to the Yuanmingyuan’s lotus pool, where they were blooming by mid-July, much to the delight of visitors. When Krasznahorkai visited the Humble Administrator’s Garden, he was told by Fang Piehe:

this garden is 500 years old. If someone takes care of a garden like this for years, after a while, he will naturally possess these [aesthetic and historical] sensibilities … Anyone who takes care of, who builds, who repairs a garden such as ours will be strongly affected by it.

The survival of this deeply conservative sentiment, notwithstanding the ravages of the Great Leap Forward and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, is cause for celebration.

Yet for all these restorative efforts the Yuanmingyuan continues to represent, to those like Ye Yanfang of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, “the most concrete evidence of Western atrocities and should be reserved as the scene of a crime”, a “lonely, desolated site [that] is a silent accusation of the aggressive acts of foreign invaders, serving as an ideal place for ‘patriotic education’”. Meanwhile, the Russian cemetery where Thomas William Bowlby and company were laid to rest was converted into the Qingnian Hu, a city park best known for its “youth lake”, dodgem cars and swinging pirate ship. The graves themselves were relocated in 1902 to what is now called the Nan Lishi Lu Park, but there they disappeared for good. As for the burial place of the general Sengge Rinchen, the Xianzhongci or “Shrine of Displaying Loyalty” in the Dongcheng District has since been incorporated into the Kuanjie Primary School. Thus the resting places of Bowlby and Rinchen have been all but forgotten, while the wreckage of the place that brought them together that fateful autumn of 1860—the Yuanmingyuan—still weighs on the Chinese collective consciousness like a fatal burthen. Perhaps that is the true reward for perfidy and cruelty, regardless of the perpetrator, be he Yizhu, Rinchen, Elgin or Mao.

To make sense of all this, one may seek solace in the foliage and rock formations of the Chinese garden, but one may also look to another perdurable aspect of Chinese tangible and intangible heritage. The Chinese Register of Ghosts, written in 1330, tells us that the “purpose of writing is to record history”, but “the purpose of theatre is to mourn the past; theatre brings those who are gone back to life and provides a forceful lesson for those who come afterward”. The names recorded in Chinese historical dramas thus become “ghosts that will never die”. It is worthwhile, then, to look to K’ung Shang-Jen’s 1699 play The Peach Blossom Fan, which describes the end of the Ming dynasty at the hands of the Manchu invaders who would become the Qing. During that conquest, the Manchu Dodo, Prince Yu, had declared “five days of unrestrained killing and rapine” in the city of Yangchow, and as the slaughter progressed, one witness observed that “the stacks of corpses had grown mountainous, but the killing and pillaging just grew more intense”. Horrible images were conveyed by the survivors:

Babies lay everywhere on the ground. The organs of those trampled like turf under horses’ hooves or people’s feet were smeared in the dirt, and the crying of those still alive filled the whole outdoors. Every gutter or pond that we passed was stacked with corpses, pillowing each other’s arms and legs. Their blood flowed into the water, and the combination of green and red was producing a spectrum of colours. The canals, too, had been filled to level with dead bodies.

Elsewhere the destruction continued apace. In Nanking the “stately Palace of the Kings was totally destroyed” by the Manchu, wrote the bystander Johann Nieuhoff, and “it is supposed that the Tatars did this for no other end or cause, but out of a particular hatred or grudge which they bore to the Family of Taiminga”. The Peach Blossom Fan draws from this deep well of memory—one the Qing could not have ignored as they watched their palaces destroyed in 1860 and then in 1900 by foreign “barbarians”—and culminates in an astonishing portrayal of the sacrifice on behalf of the civil and military martyrs of 1644, as carried out by the devout Chang Wei in the White Cloud Temple.

As the prostrations are made and triple libations are poured, and as paper, incense and culinary offerings are placed at the triple altar, the painter Ts’ai and the bookseller Lan intone:

For every martyr’s soul we pray

Who died on that ill-fated day.

All who found death by slow starvation,

Knife, or well, or strangulation,

Let no more rage your bosoms fill,

Join us here and feast at will.

“Though your bones lie tangled in thorny thickets, though your spirits flicker as will-o’-the-wisps,” Chang Wei responds, “come to our holy hill, our sacred altar”, and then his voice calls out:

Out on the dusty battlefield

With wild herbs overgrown,

Crimson stains of blood must yield

To slowly whitening bone.

In howl of wind, in rage of rain,

Homeward gazing, they gaze in vain.

Poor ghosts who linger drear and chill:

Come eat this once, come eat your fill.

It is the role of the historian, the preservationist, the dramaturge, and indeed civil society as a whole to ensure that those poor ghosts do not gaze in vain upon posterity. The offerings of grains of rice, sprinkled water and burnt paper were doubtless worthy, and so too, in their own way, are the porcelain fragments that are being pieced back together, and the long-lost lotus flowers that have only now emerged from the slumber of centuries. As K’ung Shang-Jen wrote, a “branch of pine” scattering “healing dew in droplets superfine” may prove more fitting oblations than, say, endless grievance-mongering and specious “patriotic education”. The painful laceration, the notorious “national wound” inflicted on the Old Summer Palace over the course of a century will always be felt, but the ultimate lesson of The Peach Blossom Fan should endure just the same:

Come relish pepper wine,

Breathe incense of the pine,

Lament no more the crimes of bandit rogues.

No earthly pomp can last a thousand years,

But in these hills your spirit lives forever.

Matthew Omolesky is a United States-based human rights lawyer. In the January-February 2019 issue he contributed the article “UNESCO and the Future of Cultural Patrimony”.

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search