Some young blokes, yarning in a pub back in 1521, changed a lot of the world. Interested in Martin Luther’s religious revolution in Germany, they discussed how a more moderate change would go in England. The result decades later was the Church of England and the protestantisation of the Anglosphere.

This review appeared in a recent Quadrant.

Click here to subscribe

The English Reformation, with its twists and turns of fortune, is inevitably the main theme of Lucy Wooding’s Tudor England, the latest of many histories—not to mention television programs—about this seminal century of Anglosphere development at the beginning of the modern age—if that is taken as “1492, when Columbus crossed the ocean blue” and found the Americas.

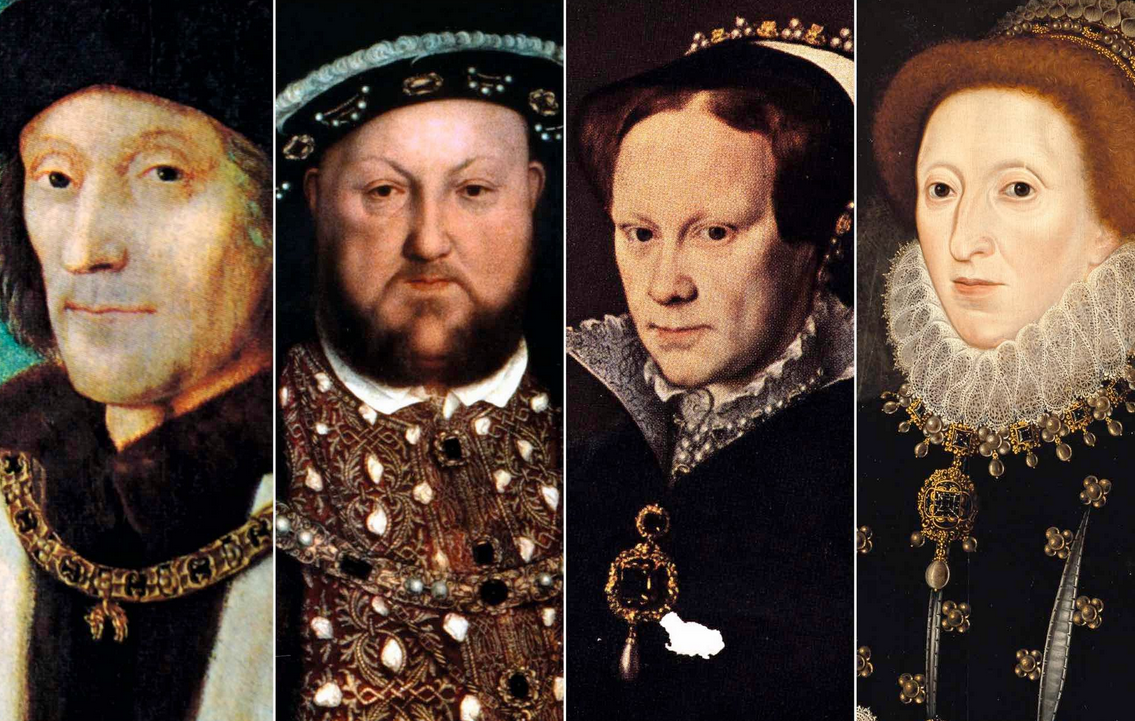

It is a very good book—fair in tone, good to read and with a vividness that can make you feel you are  there. The era starts to seem almost familiar and normal. The book is mildly revisionist, but mainly because the main players come over as fairly nice, real people—even Henry VIII and his older daughter “Bloody Mary” Tudor, let alone the glamour younger daughter, the charmer Elizabeth I, still rarely absent from a screen.

there. The era starts to seem almost familiar and normal. The book is mildly revisionist, but mainly because the main players come over as fairly nice, real people—even Henry VIII and his older daughter “Bloody Mary” Tudor, let alone the glamour younger daughter, the charmer Elizabeth I, still rarely absent from a screen.

Wooding, a tutor at Lincoln College, Oxford, keeps to the sixteenth century and does not comment or interpret much, but towards the end suggests that the strife and bloodshed of the time might have been avoidable. This is a very modern viewpoint, made possible after 400 years by the ecumenical atmosphere after the Second World War that encouraged a rethink of the religious—as distinct from political—issues involved. Clerics found that with patience, good will, theological expertise and different wording most of the issues could be resolved.

“The impact … Is usually cast in terms of division created between Catholic and Protestant; but it could equally involve division between the authorities of church and state and the people they were trying to command, instruct and control,” Wooding writes. She calls early Protestantism “effectively a protest movement” in the age-old Catholic Church that had blanketed the culture and countryside of England little challenged for a thousand years.

It was an intensely religious age, made more so by sensitivity about the after-life. The ubiquitous presence of death, especially of children, is almost incomprehensible today. Mortal disease lurked everywhere and epidemics of the plague were a regular visitation. The biggest religious divisions were over the use of English in the Bible and the Mass—both had been presented in Latin over centuries; the precise extent of papal influence over individual conscience and the related entry to Heaven; the exact nature of the Eucharist; and clerical marriage. The use of English in literature had only recently become respectable, with the invention of printing. Its use in the Bible was anathema to a church establishment accustomed to having the exclusive interpretation of the Latin Bible. Reformers saw the English Bible as allowing more lay interpretation.

The first Tudor monarch was the outside contender Henry VII. He won the crown at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 by defeating the supposedly evil Richard III, who had allegedly done away with his rivals, the princes reported to have been murdered in the Tower.

Henry was partly Welsh and ambitiously called his eldest son Arthur, a claim on the memory of the legendary King Arthur, heroic ancient British ruler of a millennium earlier. Henry married Arthur to Katherine of Aragon, niece of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, of the Brussels-based Habsburg family, the most prestigious man in all Europe for both family and position. Misfortune then struck and Arthur died aged fifteen, only five months after the glittering marriage.

Though shattered with grief, Henry had his second son, also Henry, at eighteen marry the widowed young Katherine, too valuable a bride to let go. And the long reformation drama began.

Katherine had one daughter—the future Mary I—but was unable to bear the son Henry badly wanted to succeed him. Rumours spread about Henry’s manhood. A passage in the Old Testament convinced him that it was against God’s law to marry the widow of one’s brother. He fixed his eyes on the lovely young court woman Ann Boleyn but the Pope would not grant an annulment. (It was called a divorce but in the modern sense was an annulment.) Henry believed that the Pope was unfairly biased against  him by Charles V, Katherine’s uncle. Wooding tends towards the Catholic side of the earlier story, but here she shows Henry as obsessively influenced by the desire for a son, not by the lust for Ann that many historians see, especially on the Catholic side.

him by Charles V, Katherine’s uncle. Wooding tends towards the Catholic side of the earlier story, but here she shows Henry as obsessively influenced by the desire for a son, not by the lust for Ann that many historians see, especially on the Catholic side.

Henry came under the influence of Thomas Cranmer (left), one of the clerical Cambridge pub lads mentioned earlier. He was to be the chief author of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. Cranmer convinced him that the Pope should not have so much power and that the King should be head of the Church of England. Cranmer in turn had been influenced by Luther, who believed the Bible and personal faith rather than papal decree should dominate conscience, and with it entry to Heaven.

Henry, though still a strong Catholic who loathed Luther and his heresy, was attracted to the idea of being “Supreme Head” of the Church of England and got the still fairly obedient Parliament to make him so, breaking the ancient tie with Rome. This freed him to dump Katherine and marry Ann.

He seemed to delight in his new role heading the church. Not the only politician ever to fall conscientiously in love with a personally rewarding favourite cause, he hubristically thought he could improve things. “He expected God to be equally enthusiastic,” Wooding says. He became “a highly idiosyncratic Catholic”. He made Cranmer Archbishop of Canterbury, not so much for his radical ideology but because he seemed so honest, sincere and intelligent, compared to the jostling power-seekers of the King’s usual circle.

Under Cranmer’s influence Henry allowed the newfangled English Bible to be read in churches. His really radical stroke, however, was to abolish between 1536 and 1540 hundreds of English monasteries and other religious houses, the rival power base in England. The monasteries had all but dominated England for centuries, at first as ragged rural pioneers of Christianity but by the 1500s among the great centres of wealth and power, owning parish churches, immense areas of farm land, centres of education, learning, charity and industry. A parish priest was often “the vicar”, a “vice” for the local monastery, as in vice-captain.

The dissolution, Wooding says, was “an extraordinary act of vandalism”, though some monasteries did have critics, as too big, too rich and charging farmers too much for their land. Henry moved with a touch of reforming idealism at first, as a few of the monasteries had a poor reputation. These went first, but the “dissolution” process developed its own momentum and soon they all went. The original attack turned the remaining monasteries into potential enemies of the King, while his government— like many governments since—needed the money and purchasers of monastery land would not want to risk a new monarch who might want the land back.

like many governments since—needed the money and purchasers of monastery land would not want to risk a new monarch who might want the land back.

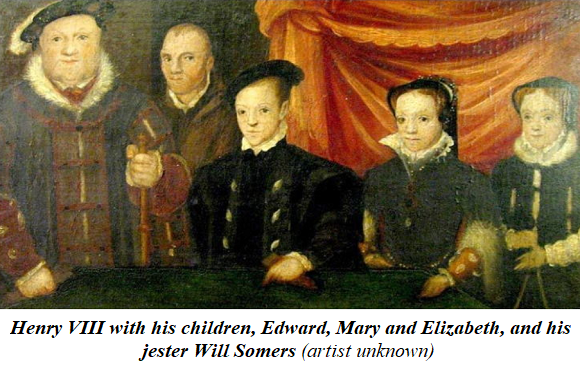

Henry’s reforming zeal began to bother his conscience as he aged. He died in 1547, still a devout if unorthodox Catholic. By then the third of his six wives, Jane Seymour, had borne his only son and heir, who became Edward VI (right) at only nine years of age. Edward had grown up with the emerging Protestant forces around Henry and was boyishly sympathetic. His uncle, the Duke of Somerset, became regent. Somerset was a disaster, trying abrasively to impose unwanted Protestant ways on the Church, including replacing the Mass with Cranmer’s prayer book—bad enough in England, but a disaster in conservative Ireland. Wooding calls him “incompetent”. The rival Duke of Norfolk led a coup against him, but was even more tactless.

Belief aside, Edward’s minders had a political motive in building up a supportive faction to guard against Edward’s half-sister Mary, next in line to the throne and a no-nonsense Catholic, who indeed was to take over when the seemingly robust Edward died of a sudden lung infection in 1553, aged fifteen.

Unlike many writers, Wooding portrays “Bloody Mary” favourably, a good, steady, competent leader taking over a still predominantly Catholic country which appreciated her drive to clean out the heretics and restore order. She spoke well of her father and was towards the reforming end of Catholicism, about to renew itself with the Counter-Reformation. To do this, however, Mary ordered the burning at the stake of 280 heretics, including Cranmer and his old Cambridge friends, who had become leaders of the emerging Protestant faction in the church.

Wooding seems strangely reticent about this aspect and also Mary’s childless marriage at thirty-eight to Philip, soon to be Habsburg King of Spain, who later was to send the Spanish Armada against her successor Elizabeth’s Protestant England. Wooding again seems to be seeing it very much through the eyes of the time, when Spain had long been England’s ally against their ancient enemy France and when fiery death for unrepentant heretics was more normal. If nothing else, though, the deaths by fire and the supposedly gallant defeat of the Armada made brilliant Protestant propaganda ever afterwards, as Wooding notes. But Elizabeth dispatched many more dissidents through hanging (some were drawn and quartered as well).

This is where Wooding most differs from A.G. Dickens’s The English Reformation, the popular modern history which is regarded as more anti-Catholic. As well as emphasising the often cruelly botched fires, Dickens also sees much more influence on the Reformation from earlier dissent. He also makes more of Philip and of London anti-clerical sentiment. Wooding says Mary would probably have returned England to a stable Catholic country, but in 1558 she died of cancer at forty-two.

Henry’s last remaining child, Elizabeth, daughter of Ann Boleyn, became Queen at the age of twenty-five. She was brought up Protestant, but was relaxed about actual religious practice. Parliament endorsed a Protestant regime but the Vatican would not accept Elizabeth as legitimate, as the daughter of Henry’s bigamous marriage to Ann Boleyn. She refused to step down in favour of her Catholic cousin Mary Queen of Scots. Soon the country was close to an angry, often hysterical religious war that disfigured most of her long reign until she died in 1603.

Despite calls for Christian charity, division and often fanaticism spread deeply through society, mixed into the other political issues of the day. Philip, Elizabeth’s half-sister’s widowed husband and King of Spain, the leading Habsburg and backed by Spain’s South American wealth, led the Catholic charge, though his family’s age-old Holy Roman Empire was disintegrating in the new Europe. The Vatican excommunicated Elizabeth with a fiercely worded Bull in 1570; Catholic subjects were required to procure her death or deposition. Though at first wavering, the Vatican had by then stiffened, with similar turmoil throughout Europe.

Despite calls for Christian charity, division and often fanaticism spread deeply through society, mixed into the other political issues of the day. Philip, Elizabeth’s half-sister’s widowed husband and King of Spain, the leading Habsburg and backed by Spain’s South American wealth, led the Catholic charge, though his family’s age-old Holy Roman Empire was disintegrating in the new Europe. The Vatican excommunicated Elizabeth with a fiercely worded Bull in 1570; Catholic subjects were required to procure her death or deposition. Though at first wavering, the Vatican had by then stiffened, with similar turmoil throughout Europe.

In England and Ireland, the resulting local uprisings, real and imagined “Catholic plots”, Spanish interventions and attempted or suspected invasions—and some very brave Catholic martyr support for the old faith—soured the Christian religion for centuries. Wooding calls Elizabeth “an outstanding ruler”, with the courage, intelligence, political skill and theatrical flair for making herself popular that kept the country at relative peace.

The result, however, was for England to become Protestant, through loyalty to Queen and country, backed by official pressure and unpopularity for Philip and the militant, at times terrorist Catholic and seemingly foreign forces opposing her. Rather than a religious revolution, Catholic England ebbed away in thousands of local churches, often undocumented. Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer replaced the Mass and the richer ritual and imagery, sometimes after transition with mixed services. The Vatican was in time to regret its dogmatic dismissal of Elizabeth and of Luther too—but it took a long time.

Tudor England: A History

by Lucy Wooding

Yale University Press, 2022, 708 pages, $61.95

Robert Murray is a journalist and frequent contributor to Quadrant on history

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search

Oh.

Thank you Robert. The Papal Bull on Elizabeth seems pretty similar to a Muslim Fatwah.

.

I guess if I had lived in the times of Henry, Mary and Elizabeth that I might have been playing musical religions every time the monarch changed.