In recent decades escalating disapproval has been directed at the discipline of Australian history. The objectivity of many authoritative books is now doubted on racial grounds, detractors alleging the books were written from too “white” a perspective. Calls have been made to remedy this via narrative histories which press an indigenous viewpoint, or, better still, are based on the eyewitness accounts of Aborigines. Especially sought is “truth-telling” where abuses by white people are revealed by the descendents of victims.

The pictures of Aunty Marlene Gilson, a senior citizen residing near Ballarat, are currently said to be answering these needs. Since taking up the brush in 2012, this Wathaurung (Wadawurrung) elder has been crafting in acrylic naive-style paintings of local life in the past. Her initial efforts on small pieces of wood were made for the entertainment of grandchildren. Then an encouraging curator chanced to see some, and there was also supportive advice from her daughter Deanne Gilson, a contemporary political artist. She began painting more cohesive pictures and her unassuming work started appearing in indigenous group shows.

Marlene Gilson’s big break came in 2015. The City of Melbourne was planning an exhibition about a legal case and subsequent execution in the early settlement during 1842. It involved a pair of Tasmanian natives convicted of murdering some whalers. Aborigines across Victoria were invited to participate in this “truth-telling” project. Under one of the council’s arts programs, Gilson landed a commission to paint a picture of the public hanging. This had not occurred in, or near, her people’s country, which lay half a day’s ride to the west. So the finished effort was a purely imagined version of early Melbourne.

During that exhibition it was argument proposed that, given the artist’s heritage, her untutored pictures revealed past events from a distinctly Aboriginal perspective. Exhibition publicity material pressed further and claimed an intellectual depth for the recognisably naive pictures: “Her paintings may initially seem charming and unassuming, but on closer inspection they reveal Gilson to be a sophisticated reader of historical events,” it stated.

This painting depicted what ambitious curators were raring to exhibit: colonial capital punishment being dished out to Aborigines. In no time the picture had been slotted into a sequence of political art shows, including “Sovereignty” at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, “Frontier Wars” at the National Gallery of Victoria, and “The Art of Tasmania’s Black Wars” sent on a national tour by the National Gallery of Australia.

The former hobby painter was soon taken on by a commercial gallery in Sydney. Gilson settled into manufacturing naive views of the gold rush at Ballarat. Most marketable were her pictures of the historic clash at the Eureka Stockade, which she has painted more than five times—they go straight into institutional and major private collections.

It now began to be said that Gilson based her art upon precise oral histories carefully passed down over centuries through her mother’s family. Thus her work was talked of in the museum sector as a significant new contribution to “the field of historical narrative painting”, with exalted claims made on its display of intellect. Some art curators advanced the line that the septuagenarian artist’s naivety may be a ruse, and that behind a surface simplicity were the efforts of a postmodern deconstructionist.

The Art Gallery of New South Wales states that Gilson’s naive pictures “question the colonial grasp on the past by reclaiming and recontextualising the representation of historical events”. This sounds imposing, but it consists of hollow phrases—a suspicion confirmed by the lack of any explanation on how those pictures question, reclaim and recontextualise. Still, a cluster of other museums now quote, and even mimic that sentence in their own publicity. Like Ballarat’s Eureka Centre, which owns a fetching Gilson view of the 1850s goldfields. This popular tourist centre assures visitors that her works “overturn the colonial grasp on the past”, along with further exalted claims about reframing history. Again no clarification is offered, as if all can see the Emperor’s splendid new costume.

Esteem for Gilson’s work was boosted exponentially in 2018 when she completed The Landing. Another instance of “truth-telling”, it portrayed an event some 250 years ago as purportedly witnessed by Aborigines—Captain Cook’s visit to Botany Bay in April 1770. Featured in the prestigious Biennale of Sydney, The Landing was unveiled before an international audience. Given the 250th centenary of Cook’s visit was coming up, this historical picture shot to instant renown, and was purchased by the National Gallery of Victoria. Again the event portrayed had not occurred anywhere near Gilson’s tribal country. Nonetheless her picture was acclaimed as a solid Aboriginal witness statement. “Her recounting of events poses an alternative to sanctioned or official chronicles, disrupting the prevailing colonial view that dominates Australian history,” ran the Biennale’s gush. What led Gilson to depict a subject with no connection to her tribal forebears was not explained.

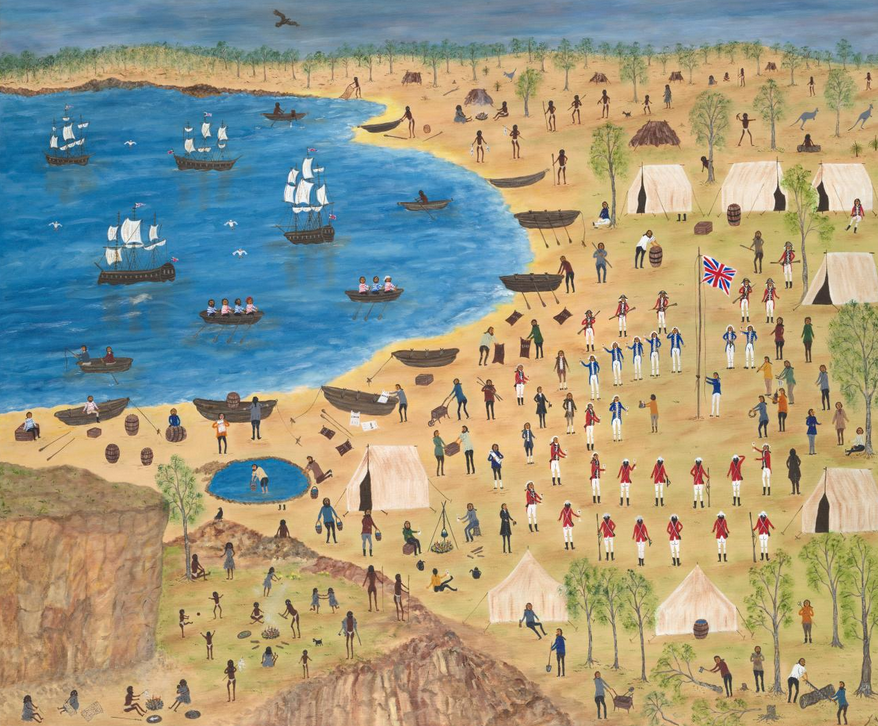

The Landing is a highly entertaining instance of naive art. Younger children especially enjoy pointing out the many little people in the scene and telling you what activities they are undertaking. Gilson depicts Cook and a military party taking possession of Australia at a beach camp—the first European settlement. Rowboats are drawn up on the sands and tents pitched in a protective circle with a slender flagpole set in its centre. Uniformed marines stand at attention as a naval officer raises the British flag. This formal parade is watched from the side by more naval officers and gentlemen in suits.

Meanwhile, a scene of restless animation appears around the camp. Figures spread out in an even scatter. We see the ship’s crew cutting down trees, gathering fuel, foraging for food, filling barrels with fresh water, fishing from two rowboats, and attending to assorted tasks. Further out still, among shrubs and trees, Gilson shows Aborigines going about daily activities oblivious to the European visitors taking over the land.

This composition is so crammed with activity viewers might be forgiven for not initially noticing how much is amiss. Cook did not take possession of Australia at Botany Bay; nor did he set up a camp there. Then you notice, and count, the number of tall ships anchored in the bay, and those assertions about Gilson “questioning”, “overturning” and “disrupting” any view of the past crumble upon themselves. Instead of travelling the South Seas on a single vessel, the famed Endeavour, Gilson has Captain Cook in command of four sailing ships! This work portrays Cook visiting Australia in 1770, accompanied by three vessels from the First Fleet in 1788.

On inspection it is obvious that far from presenting Cook’s arrival in Botany Bay in a revealing way, this Aboriginal version of events gets facts wrong. Many, many facts wrong. A list of shortcomings seems needed, given the claims made for what is a naive picture which muddles the explorer’s visit with a different historical event.

Not only the number of ships shown is incorrect. Twenty-three marines and nine naval officers appear in the picture. But a dozen marines were assigned to the vessel, while, as well as Cook himself, there were five officers on board: Lieutenant John Gore, Lieutenant Zachary Hicks, the midshipmen Charles Clerke and Richard Pickersgill, and the ship’s surgeon Dr William Monkhouse (technically, he was a petty officer). Likewise when counting off the tars shown busily working all around the picture, the crew is too large. The Endeavour’s foredeck could not accommodate so many people and their provisions.

As the inquisitive eye wanders, errors mount. The sailors did not fish with rods at Botany Bay; they used a fishing net, pulling in each day a weighty catch (including plump stingrays) with just a couple of hauls. Nor were eight rowboats carried on the Endeavour. It had a pinnace and a yawl. As for the eight huge tents shown pitched on the sands, for safety Cook ordered all his men to sleep aboard the Endeavour each night. For the same reason, in daylight hours the men went ashore and worked in small parties closely supervised by petty officers and protective marines. What we are shown is seriously wrong.

Much as the camp portrayed is a fiction, so too is that flagpole Gilson shows erected on the beach. A flag was raised and flown ashore each day—from a tree. About those marines attending the parade, they were not bare-headed with white powder in their hair as shown. They wore shakos, those distinctive black military hats which were part of their uniform. Worse still, that British flag in the picture did not exist in 1770. Gilson has painted a Union Flag which was introduced thirty years later upon the Act of Union in 1801.

Kangaroos hop by the camp. But no such creatures were glimpsed by Cook’s men at Botany Bay. The first sightings, of wallabies on grassy river flats, happened months later along the Endeavour River. Gilson’s naive painting even has the wind behaving bizarrely. Filling the billowing sails on those four ships, it blows from right to left; yet making the flags on the same vessels flap in the opposite direction, it also blows from left to right.

Most telling about the picture’s reputed accuracy is what it does not show. On several occasions Aborigines confronted the Europeans, throwing spears while shouting they should go away. Not shown. Each day during the Endeavour’s visit Aborigines went down to the water and spear-fished, as well as gathering oysters and shellfish. Not shown. Then there was the funeral and burial on the beach of Forby Sutherland, a seaman who died of tuberculosis overnight on May 30. The Aborigines watched the service intently, but it is not shown.

Stranger still, Gilson leaves out the scientific and survey work which was the reason for the voyage. The naval officers are not surveying and making a map of Botany Bay. The botanists Daniel Solander, Joseph Banks and their expert assistants are not hunting for plants and flowers in this new land. The astronomer Charles Green and expedition’s technician Herman Spöring have not set up the telescopes to study stars in Southern skies.

The Landing is an obvious confection, a fictional scene, and it raises a simple question. Does the artist have a poor grasp of history due to limited schooling, and mistakenly thinks this is what happened? She would not be the only person ignorant about the facts of Cook’s expeditions. Or might this naive scene be allegorical, an effort by the painter to make a symbolic connection about James Cook and the First Fleet? An explanation is surely needed.

Public museums refrain from accounting for the visible errors in pictures like The Landing. Instead of addressing Gilson’s defective history, curators engage in word games. When, earlier this year, the picture of Cook at Botany Bay with the First Fleet in 1770 was included in a show at Bendigo Art Gallery, an impenetrable wall text declared its consequence. Of the composition’s design, it stated:

Eurocentric artistic imaginations of this event usually revolve around Cook as the dramatic central protagonist, but in Gilson’s painting each figure is equivalent in size and importance, emphasising the multiplicity of history and the complex interconnectedness of human lives.

This reads as if written by a person straining to be clever. The sentence is overcrowded with words, running much too long. It also tries to keep the best idea until the end, aiming to impress you with a brilliant point. These are moves typical of art administrators out of their depth and arguing a weak case. The sentence is a cultural bluff, giving itself away with the phrases “multiplicity of history” and “complex interconnectedness”. Those concluding terms are meaningless fill, which is why they are not expanded upon.

This analysis is so obviously wrong. The picture’s design does make Cook and his officers central protagonists in the drama, not the reverse. Gilson brings this off by using the circular shape of Cook’s camp to catch the eye and draw it in. This talented naive painter positions the flagpole in that shape’s centre. This is calculated to make the viewer look at the flag-raising ceremony. So the text presents a political argument which Gilson’s measured picture is visibly not advancing.

Some public institutions applaud Gilson’s work as if the historical mistakes are meritorious. Take the Shepparton Art Museum in regional Victoria, which purchased another Cook picture painted by Gilson. This second naive work, a quite cluttered composition, depicts the First Fleet under the command of Captain Cook settling Australia in January 1788.

Interviewed by the town newspaper about what was a controversial acquisition, the museum’s director Dr Rebecca Coates called Gilson’s eccentric picture a “powerful” work. Continuing on, the curator made the bold claim that this portrayal “challenged mainstream historical narratives” by depicting Cook with the First Fleet at Botany Bay during 1788.

This is sophistry. If a student taking a history test makes a basic mistake—for instance, having General Washington cross the Rubicon—we acknowledge and treat this as incorrect. They cannot pass the exam by claiming to have challenged mainstream history. That would be absurd. As for James Cook, he died in Hawaii nine years before the First Fleet even set sail. Yet Dr Coates neither accounted for his presence in the scene, nor explained how the work “challenged” the discipline of history. An attempt at interpretation is in order, and not just for the benefit of the perplexed. That exalted claim begs to be proven: show us how the picture does this to justify the effort and expense of purchasing it. But Shepparton Art Museum did not, and has posted the newspaper report on its website instead of offering a proper artistic analysis.

As a literal representation of the historical event, Marlene Gilson’s picture is false and misleading. To point this out is neither racist nor politically incorrect. It is common sense, a matter of historical accuracy, Cook having no contact whatsoever with the First Fleet. In no way does Marlene Gilson’s Aboriginality have a bearing on the issue. Ethnicity and racial identity do not cause events to shift their temporal location. The blunt facts are unchanged, and to repeat without correction or explanation her erroneous story that Cook accompanied the First Fleet to Australia is to knowingly spread disinformation.

However, when either of her Cook paintings is exhibited in public museums the supporting labels and wall texts treat Gilson as correct in what she portrays: as if Cook was with the First Fleet. School parties, visitors and tourists are assured by gallery staff there is nothing odd with the pictures’ presentation of history. When viewing The Landing in an exhibition, I saw a gallery guide tell Asian students this is Australia’s history. Not even information on museum websites admits there are inaccuracies in Gilson’s historical scenes.

The insistence across public museums that Marlene Gilson’s art is factual affects how it is categorised, the genre it sits within. Ordinarily such work would be classed as Naive Art. But much is at stake in intimating Gilson’s pictures amount to information relayed from natives in past times. So the museum sector categorises her work as Contemporary Aboriginal Art, downplaying or just ignoring anything characteristic of Naive Art. Exhibition labels and curators’ essays even caution viewers not to be misled by a “naive style and colourful palette”.

Curatorial discussion on Marlene Gilson avoids the Wadawurrung, her tribal forebears. The Wadawurrung and the neighbouring Djab Wurrung were feared in early Victoria. William Buckley’s memoirs report them as most aggressive, and practising ritual cannibalism. Both tribes routinely ambushed Europeans either heading to or coming from South Australia, usually accosting small groups of solitary travellers in the lonely wilderness between Buninyong and the Grampians. During the 1840s my great-great-great grandparents walked from Adelaide to Corio without incident in that dangerous corridor because they travelled in a large party—safety in numbers.

During the following decade the Wadawurrung and Djab Wurrung targeted people on the move to the many new goldfields west and north-west of Melbourne. There was alarm among miners as word of these attacks circulated, and it motivated the commercial artist S.T. Gill, who was recording life at the Ballarat diggings in 1854, to compose a drawing of human remains decaying on a desolate track out of Buninyong. Especially vulnerable to native attack was that stream of Chinese who hiked several hundred kilometres from coastal Robe to the Ballarat diggings and beyond. The Aborigines were brutal with the Chinese, eating some of their victims, who they notoriously said tasted “like pork”.

Gilson’s pictures of the 1850s do not show natives preying upon travellers, let alone killing Chinese making for the goldfields. This should not prevent art museums from explaining the history of the Wadawurrung during the period repeatedly portrayed. Museums never do this. They do not mention Aboriginal attacks on prospectors.

Museums do briefly outline whichever historical event is portrayed in a Gilson picture. But what they say is not necessarily correct. History will be twisted about. At the Biennale of Sydney in 2018 the text supporting a Gilson painting of the Eureka Stockade stated the rebellion portrayed had been a workers’ uprising. This is preposterous. Workers had not risen against employers. As every Australian history student knows, individual prospectors were aggrieved over the government’s stringent licensing arrangements for self-employed miners working their own claims.

Bendigo Art Gallery used the occasion of exhibiting Gilson’s painting of Cook and the First Fleet at Botany Bay to rewrite Australian history. It hung The Landing at the beginning of the exhibition adjacent to a selection of tribal Aboriginal artefacts collected locally, including spears, baskets, spear throwers and a boomerang. This made a strong visual introduction.

However, wall texts displayed through that exhibition arbitrarily changed Australian history with no regard for evidence. One declared that Australia was a “sustainably managed land” before white settlement. Hunting our megafauna into extinction surely does not square with this statement. Another text railed against Federation for imposing upon the nation an “implanted government”. Details were not supplied. Another text asserted that Aborigines were not entitled to vote in Australia until “several decades” after Federation. This is manifestly wrong. Aborigines were given the vote in Victoria, New South Wales and Tasmania in the late 1850s, a time when—as Geoffrey Blainey has pointed out—fewer than 1 per cent of the world’s population enjoyed the right to vote.

Bendigo Art Gallery’s rewrite of Australian history cancelled even information fundamental to the labour movement. This was most pronounced with a text explaining the major painting Shearing the Rams by Tom Roberts, which was also displayed in the exhibition. It said nothing about the mighty controversy which greeted this work when first exhibited—a time of protracted strikes over the introduction of mechanical shears. Given how Roberts deliberately heroised men using hand shears, his painting was widely suspected of supporting the shearing union’s demands. Ignoring all this, which is fundamental to what Roberts was alluding to with his picture, Bendigo’s interpretive text instead proceeded to blame the wool industry for environmental degradation across Australia.

With her success in the museum sector, and joining a Sydney commercial gallery, Gilson settled into steadily painting the 1850s Ballarat goldfields. But those naive pictures do not show plausible diggings. No one, not a single prospector, is seen in them panning for gold on alluvial flats. Absent too from along her creeks are the many small dams, channels and sluices made and used by miners. Also omitted are larger mechanisms collectively made and used; like a puddler, which miners would use to separate heavy earth from ore-bearing sediments, and simple crushing devices to break the gold-bearing quartz.

Most striking about Gilson’s goldfields is how they are not covered with a multitude of individual claims. By law each prospector had to stake out his claim. So her views should be dotted with markers and signs, especially beside patches of excavated earth, shallow shafts and mullock heaps, those characteristic mounds of tailings. Likewise the network of criss-crossing dirt paths, rutted tracks and muddy roadways which threaded through active goldfields are not shown, while trees and shrubs—which were quickly thinned out, in places clear-felled—spread evenly in Gilson’s backgrounds. This is not how things were, not at all how they were. We know this from the drawings, watercolours and lithographs of journalist-artists like S.T. Gill who went onto the goldfields to report visually on what was taking place for the print media.

Instead of disorderly clutter, what Gilson paints are neatly laundered white tents and rough-hewn huts, with one small, solitary shaft sunk somewhere in middle ground and tailings piled adjacent to it—just a single mine usually in the entire picture. Meanwhile, little people go through a repertoire of pointless actions right across each scene. Some bear shovels, but no one is digging for gold or prospecting. In the foreground of several canvases there are even Chinese figures who—instead of mining—busily tend vegetable plots.

Meanwhile at the edge of the diggings there will be a number of Aborigines, who are leading a traditional life seemingly unaffected by how their land has been taken over. It stretches credibility to claim Gilson’s pictures give a real sense of how Aborigines felt about the goldfields, let alone that she is relying on knowledge passed down between generations. Consider her painting which has Aboriginal men performing a corroboree beside the Eureka Stockade even as fighting there is taking place. This simply did not occur.

That Marlene Gilson is of indigenous descent ought not to affect the value ascribed to her naive pictures, those child-like scenes with a touch of fantasy, any more than if she was of other background. As for declaring that her paintings destabilise Australian history, this is unwarranted and potentially exposes the artist to needless criticism. Of course, there will always be viewers who, unable to see beyond Gilson’s cultural identity, attempt to impose meanings upon such work. But when held up to the pictures themselves, much of what is intellectually claimed for them does not correspond with what has been visualised.

Recognising Gilson as a naive artist would settle much. Besides a lack of aesthetic sophistication, swerves away from strict fact are common among naive painters. From Henri Rousseau’s tropical jungles to Alfred Wallis’s ships plying tilted oceans to Henri Bastin’s flowering deserts, we savour and enjoy these moments of visual fantasy. Departing from fact is intrinsic to the self-taught creator’s unrefined vision, indeed, it is why their oeuvre is classified as naive. The element of fantasy is a distinguishing feature, being central to such paintings’ abiding charm.

It is usual for a naive artist to have taken up the brush late in life, often after they have ceased regular work. Their untutored pictures strike us as childlike not just due to flawed technique, that lack of perspective and visual proportion, the clumsiness to forms. It is chiefly conveyed by an innocence about the scenes shown, how there is neither cruelty nor evil in this imagined realm. Happiness reigns. This is because the naive artist is painting what they love. Each fantasy will be made by borrowing cherished aspects from their known world: with Rousseau it was the gardens and parklands of Paris, Wallis took from the Cornish sea trade, Bastin from the desert near Coober Pedy after rains.

Marlene Gilson began painting in her early seventies following a spell of ill health. She had been living for some years in the Gordon–Mount Egerton district, a small sleepy hollow about eighty kilometres west of Melbourne, not far from Ballarat. Her early run of naive paintings traded in past happenings from nearby Buninyong, down to Victoria’s Surf Coast, and across to the Bellarine Peninsula. This is the place she knows and loves, her home country.

Indicating sky on each picture with a bright blue strip painted along the top, Gilson then lays out landscapes as if she is placing items on a table top. Trees, tents, huts and humpies are schematic, not naturalistic, while a creek is denoted with another bright blue band, this one curving across the view. She then sets down a pattern-like crowd, the little figures set evenly at regular intervals across picture. Some flat men stand in static rows, but most perform activities. A figure will carry a shovel, or a bucket, a basket, a bag, some flowers, vegetables, a stick, a gun; another figure will be walking, or dancing, running, hopping, riding a horse; and some people tend vegetable plots, or cook at open fires, or rise from a mineshaft. Gilson avoids showing violence. Apart from in her pictures of the Eureka Stockade, figures do not fight or attack one another. Whether they are Aboriginal, European or Chinese, people are shown getting along together.

Marlene Gilson is at her best creatively when left to her own devices. She excels at views of Aboriginal life, of seasonal camps, of beach gatherings, as well as the beginnings of gold mining, local race meetings, sports club barbecues, always in the rural district where she lives. Some incidents in Gilson’s paintings certainly came from family, but she does dip into a communal fund of folklore and memories. Everyone in the community speaks of the bushranger Captain Moonlight who robbed the Mount Egerton bank; several Eureka rebels also lived locally; a certain house is said to be haunted. The district is rich with tales, so people and places lifted from local legend will appear as quirky details in her homespun pictures, much to the amusement of other residents. Representation plays quite a part in Marlene Gilson’s infectiously entertaining works, but so does invention. They are self-evidently pictures from an untutored yet talented hand, from a joyously fertile imagination, from one who paints what she cherishes.

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search