If Martians had landed on the front beach of my home town in the middle of my childhood, a small boy and his dog (Larry) would have been straight down to see what they were doing. Also present would have been Mr Porter the policeman, Councillor Golightly the mayor, and possibly Eddie George, the proprietor of Eddie’s Store, to measure them up for winter jumpers or summer bathers. It would have been a welcome of curiosity, authority and commerce. It wasn’t like that in Botany Bay in 1770.

Michael Connor appears in very Quadrant.

Click here to subscribe

The landing point of the Endeavour in Botany Bay has become the launching point for Australiaphobia, and the use of the word discovery a stimulus for Elmer Gantry piety. Stan Grant miserabilising on a memorial statue of Cook is pitch perfect, even as he forgets that his forebears were both on the shore and on the ship:

My ancestors were here when Cook dropped anchor. We know now that the first peoples of this continent had been here for at least 65,000 years, for us the beginning of human time. Yet this statue speaks to emptiness, it speaks to our invisibility; it says that nothing truly mattered, nothing truly counted until a white sailor first walked on these shores.

Last year I was in France and discovered Bordeaux—both in the bottle and on the banks of the Garonne. I don’t mean that Bordeaux the place was either unowned or unpeopled, and when the first claim of discovery was made by young Sydney Parkinson not a single member of the crew had stepped into the Australian landscape or noticed the presence or absence of local Aborigines. In April 1770 the Endeavour was sailing westwards after leaving New Zealand and Parkinson was writing his journal: “We continued our course, but nothing worthy of note occurred till the 19th, in the morning, and then we discovered the land of New Holland, extending a great way to the south, and to the eastward.” The influence of the discovery denialists is strong. Ask Microsoft Bing if Cook discovered Australia and the AI response is sure and wrong: “No, the idea that Captain Cook discovered Australia has long been debunked.”

As the Endeavour entered Botany Bay figures were seen near a fire. Noticing the ship, they moved to a hill offering a better view. A boat was lowered to sound the waters the Endeavour was entering and this was followed in its course by natives on the shore. No one on the beach waved: several armed men made threatening motions. Near the bay entrance were four canoes whose occupants were fishing and took no notice of the ship. Were Aborigines accustomed to looking out to sea, or were they more concerned to keep a watch inland from where danger could arise? It is a question which recurs as Cook sailed along the east coast, sometimes remarking on the lack of interest in his very interesting Endeavour. Banks wondered if these men were deafened by the sounds of the surf and had not noticed them. Perhaps they were hungry and fish were present. At one point the canoes returned to the shore and the catch was immediately prepared for eating, everyone seemingly unconcerned with the presence of the Endeavour about half a mile distant.

Cook attempted to make contact but was rebuffed. Parkinson wrote that the locals called out something sounding like “Warra warra wai” and threw spears and stones. It was not very welcoming. For a long time we all thought those strange words meant “Go away” but now modern attempts to recreate the language spoken by the people on the shore claim the words mean “You’re all dead” and suggest the people believed they were seeing spirits on the big canoe. At an earlier time, before moderns invented “oral history”, Aboriginal testimony suggested the men climbing the ship’s rigging were thought to have been giant possums.

The new translation is interesting but, like so much of our reinvented race history, is uncertain because those same words were heard in other early contacts around Australia where very different languages were spoken. The historian Keith Vincent Smith has noted that “Warra wai” was recorded at times of first contact in Botany Bay in 1770, in both Botany Bay and Sydney Cove in 1788, Oyster Bay in Tasmania in 1791, and in Western Australia at the Swan River in 1829. Smith also cites a family letter by Daniel Southwell, written at Sydney Cove in 1788, which gives a different impression of the usage: “The ships saluted at sunrise, noon and sunset, which must have frightened the warra warras, for so we call the blacks, from their constant cry of ‘warra’ at everything they see that is new.”

When the Endeavour moored in Botany Bay, Cook asked for help, in a search for water, and was refused—violently. This is Joseph Banks’s account of what took place (spellings have been modernised):

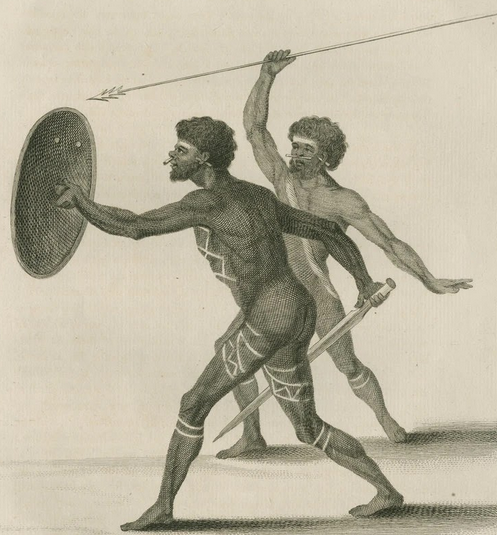

After dinner the boats were manned and we set out from the ship intending to land at the place where we saw these people [a group watching from the shore], hoping that as they regarded the ship’s coming in to the bay so little they would as little regard our landing. We were in this however mistaken, for as soon as we approached the rocks two of the men came down upon them, each armed with a lance of about 10 feet long and a short stick which he seemed to handle as if it was a machine to throw the lance. They called to us very loud in a harsh sounding Language of which neither us or Tupia [the Tahitian travelling with Cook] understood a word, shaking their lances and menacing, in all appearance resolved to dispute our landing to the utmost though they were but two and we 30 or 40 at least. In this manner we parleyed with them for about a quarter of an hour, they waving to us to be gone, we again signing that we wanted water and that we meant them no harm. They remained resolute so a musket was fired over them, the Effect of which was that the Youngest of the two dropped a bundle of lances on the rock at the instant in which he heard the report; he however snatched them up again and both renewed their threats and opposition. A Musket loaded with small shot was now fired at the Eldest of the two who was about 40 yards from the boat; it struck him on the legs but he minded it very little so another was immediately fired at him; on this he ran up to the house about 100 yards distant and soon returned with a shield. In the mean time we had landed on the rock. He immediately threw a lance at us and the young man another which fell among the thickest of us but hurt nobody; 2 more muskets with small shot were then fired at them on which the Eldest threw one more lance and then ran away as did the other.

What had occurred at this moment when the British met the locals?

Theresa Ardler, an activist who wants to “change the story”, offered her history on the ABC:

I was in high school in Year 10 studying Cook, and we were reading a book that said the bullets were fired over their heads. I remember getting up in my class and saying, “This is wrong, this is not the true history”, because my grandfather was shot. I said everyone needs to rip that page out of your book.

Stan Grant used the politics of Mabo and “frontier history” to turn what happened into what should have happened at Botany Bay: “These were sovereign people defending their country from an invader.”

The National Museum of Australia is brisk:

Attempts to communicate failed, so Cook’s party forced a landing under gunfire. After one of the men was shot and injured, the Gweagal retreated. Cook and his men then entered their camp. They took artefacts and left trinkets in exchange. Seven days later, after little further interaction with Gweagal people, the Endeavour’s crew sailed away.

Neither Ardler, Grant nor the Museum mention the children. Banks’s account—and the journals of Cook and Parkinson are similar—continues just after the two warriors have run off:

We went up to the houses, in one of which we found the children hid behind the shield and a piece of bark in one of the houses. We were conscious from the distance the people had been from us when we fired that the shot could have done them no material harm; we therefore resolved to leave the children on the spot without even opening their shelter. We therefore threw into the house to them some beads, ribbands, cloths etc. as presents and went away. We however thought it no improper measure to take away with us all the lances which we could find about the houses, amounting in number to forty or fifty.

What sort of parents abandon their children like this? The camp kids, surely used to wandering freely about, have been placed in a house—Parkinson’s sketch shows a rough shelter of branches. Have they been deserted or forgotten by their fearful and careless parents? Surely their placement and confinement are deliberate. They, and the shield and the spears, may have been left as an offering to the spirits. Hungry white ghosts, who had not been frightened away, have been provided food, and weapons for hunting. Ray Ingrey, a representative of modern Botany Bay Aborigines, endorses the supposition that his forebears believed they were dealing with beings returned from the dead: “So when the two men opposed the landing, they were protecting the country in a spiritual way, from ghosts.” From an Aboriginal perspective the children were not “found” by Cook and Banks, they were “given” by the Aborigines to famished spirits. In late autumn everyone may have been hungry.

Modern activists might be more accepting of Cook if he had recognised Aboriginal customs by eating the children. To do so would have been a form of communion between the English navigator and the Botany Bay locals. It would have made a fine drawing for Sydney Parkinson and a fine anthropological paragraph in Banks’s journal. The modern oral history would be marvellous and, for historians, a superb balance with Cook’s own fate.

In Botany Bay the Endeavour met violence and irresponsibility. Cook behaved cautiously. Firing on the two threatening men was a reasonable response. It was not vicious or bloodthirsty and it would not have happened if the people on the shore had approached the strangers with caution and friendliness. The Aborigines showed they were culturally incapable of dealing with outsiders without invoking their own rules of violence. There was no authority for Cook to deal with. Interest was certainly present on the Aboriginal side but it never led to an organised response or even individuals, including curious boys (with or without dogs), to approach the crew with human warmth, and the fault lay with the locals. Joseph Banks, after a week of non-involvement by the Aborigines, offered a searing opinion of their behaviour: “4 May 1770—Myself in the woods botanizing as usual, now quite void of fear as our neighbours have turned out such rank cowards.”

If we are to see the past from both perspectives, as so many of us wish, then the original brutality of Aboriginal life has to be investigated and brought into our history writing. An inclusive ship-and-shore history needs truth, not invented oral histories, which should be named and removed.

Modern accounts which politely and politically ignore Aboriginal brutality are self-indulgent, politically motivated and utterly boring. The Sydney Gazette began publication on March 5, 1803, and on Christmas Day that year published this story—it may be the first time you have read it:

A circumstance that lately took place at Milkmaid Reach, on the Coast between Sydney and Hawkesbury, among a body of Natives, stands, in point of deliberate inhumanity towards a fellow creature, unparalleled save only in the barbarous usages to which these people are habituated. One of their number had climbed a lofty tree in pursuit of a Cockatoo; and as soon as he gained the summit and had secured the bird, unfortunately got entangled in the twigs, and in trying to disentangle himself, lost his hold, and by a tremendous fall had both a leg and thigh broke. The women at the instant set up a piercing shriek, and the men assembled around him. The elders examined the fractures minutely, and pronouncing them incurable, hastily commanded the females to retire; then erecting a pile of brush-wood about the body, actually set it on fire, whilst the unhappy creature was alive. As soon as this inhuman but effectual remedy was administered, the Boatmen who were spectators of the proceedings, were advised by one of the more friendly natives to get off as quickly as possible, as the fatal event had aroused the indignation of the whole tribe against all white people, as the Cockatoo would not have been climbed for, had not a reward been the known consequence of its capture.

If today my Martians landed in suburban Sydney or Melbourne they would be met by foreskin inspectors disguised as anti-Zionists, climate protesters, Islamic clerics, Middle Eastern and African gangs, and Pascoeites selling smoke ceremonies. This welcoming committee would represent our intellectual elite, the authorities on our streets, and commercial interests. This time it may be the visitors who say “Warra warra wai”.

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search

When Australia was separated from Asia the aboriginal people thus isolated would have the skills they had learned from their ancestors. They did not progress in any substantial way and were not the noble savage that those of aboriginal descent would have us believe. They were a violent people who had no respect for human life It seems to substantiated in the writings of those who first came to Australian shores.

Thank you Michael,

fascinating story about the cockatoo. It reminds me that colonial newspapers and journals are valuable source of information, because in those days, they recorded facts not opinion. And stories of Aborigines wronged abound. There was no conspiracy to cover up atrocities.

From the diaries and journals written of that time at Botany Bay, a week or so, it is clear from the encounters that there was no council of elders or representative authority to parley with the Brits, nor was there a “Welcome to Country” or “Smoking” ceremony performed.

.

The hostility born of fear shown by the two men on the shore in no way can be interpreted as the actions of “warriors” defending their sovereign nation, as the “Truth Tellers” now inform us. The men actually had fishing spears with them and no shields. While the Endeavour party were still in the boats, it was Banks who raised the caution that the spears may have poison on them, but upon coming ashore and examining the spears, he learned that what he thought was a poison-soaked wrap around the barbs was in fact seaweed.

.

Later that day on the north side of the bay, Cook’s party communicated with some people on the shore, signaling their want of water, and were directed to a spot where fresh water was available.

.

Later that week while exploring the estuary to the south-east of the bay, a number of local men came to the boats and were very friendly and excited, and pointed to the shore where the women and girls were standing, and communicated by obvious gestures that the Brits were free to avail themselves of the females. There may not have been a smoking ceremony, but it certainly can be understood to be a “Welcome to Country”!

Yes in dee dee!

Welcome to Country

““No, the idea that Captain Cook discovered Australia has long been debunked.”

True. Cook (and his crew) discovered New Holland.

They would have been insulted by Cook and his men refusing the gift feast of the children.

Seriously, the stories the revisionists “historians” hatch up would be hilarious, were they not taken seriously. They have the credibility of Hans Christian Andersen or the Brothers Grimm.

When Cook and Co. were within spear range, Cook fired a musket over the head of an Aborigine – for what reason? What would a bullet passing harmlessly over the head of an Aborigine have?

Supposing the almost impossible happened, the Aborigine was wounded. Might the Aborigines have responded with a shower of spears, rocks, or both, landing in the boat?

That a weapon was fired is not questioned, the reason was almost certainly for the noise effect. At the “Risdon Massacre” we are told, a three-hour battle between 15 soldiers and 300 Aborigines took place. After 50 Aborigines had been massacred whilst failing to inflict even a scratch on their enemies, the sound of a carronade caused them to flee.

Shortly after the Risdon “massacre” of Aborigines, at George Town, a conflict between over 80 Aborigines and three soldiers saw the Aborigines flee when two shots were fired, killing one Aborigine and wounding another.

Yet another Tasmanian story has four VDL workers achieving the impossible. After descending a steep path, ambushed 30 Aborigines – clearly impossible, yet they came sufficiently close to the Aborigines to be able to kill them all with a sequence of shots from rifles known for inaccuracy over distance.

The Aborigines, enjoying a meal of seafood on a beach did nothing in the 20 second interval when, by then, they had leaned that the rifles were temporarily useless. Although able to see the enemy, they remained in the area.

The Aborigines in this area were known to be more ferocious than those at Risdon, yet when they could see that the odds were 26:4 in their favour, they put up no self defence!

When the Aborigines were all dead, their bodies were thrown over a 200 foot cliff!

One “historian” spotted the error.

The original story was slightly adjusted, with the Aborigines moved uphill and the menu changed from seafood to mutton birds.

I understand that one of the journals (it may have been Bank’s) described the preparation for the landing. Apparently, Cook instructed the party to load the rifles with birdshot. This would frighten but minimise any damage. This would be consistent with the text above, “ A Musket loaded with small shot was now fired at the Eldest of the two who was about 40 yards from the boat; it struck him on the legs but he minded it very little ”.

Clearly, there was no attempt to harm.

Well, I am no apologist for Aboriginal customs – there are what they are. But I certainly deplore the decision of Cook’s party to confiscate “ forty or fifty” of the natives’ spears. Such weapons were arduously made and relied upon for sustenance. I find this evidence perplexing, as Cook, Philip & other commanders of their generation were almost universally careful not to destroy the possessions of indigenous peoples they came across.

Unsubstantiated references to cannibalism are just outright racist.

Complaint made to press council for racial vilification.

Is Quadrant even a member of the press council?

The Audtralian Aboriginals were certainly cannibals. To confirm, read the first hand report of Englishman William Buckley, a young escaped convict in 1803 Victoria, who, to survive lived with an Aboriginal tribe around Port Phillip Bay for about 30 years. His factual account has been recorded by John Morgan the retired editor of the Hobart Times, and published in 1852 .Buckley confirms the cannibalism of the Aboriginal savages.

If today my Martians landed in suburban Sydney or Melbourne they would be met by foreskin inspectors disguised as anti-Zionists, climate protesters, Islamic clerics, Middle Eastern and African gangs, and Pascoeites selling smoke ceremonies. This welcoming committee would represent our intellectual elite, the authorities on our streets, and commercial interests. This time it may be the visitors who say “Warra warra wai”.

A surprise ending to an interesting article!

Thank you Michael, these journals and papers are our best source of the truth of this normal human discovery. The emotional fiction from revisionists are filling Australians heads with demoralising rubbish. Best to ignore it as much as possible for one’s sanity.

Can Aboriginal corporations et al. not see many a good indigenous Englishman, Irishman, Italian, Grecian German, Vietnamese etc, has left family, left homes, left languages to move here permanently? They do realise that all who move here are indigenous to an original land right? Surely? Have several million Aborigines left behind Australia and their parents/brothers/sisters to settle elsewhere? How would they like it if they and children born in their new country were forever bombarded minute-by-minute with declarations that they ‘work and play’ on say.. Spanish land? A bit of their own medicine perhaps?

It wasn’t my choice to be born here. If I had my way I would move back to an indigenous country of my ancestry, free from this sick brainwashing. But I cannot destroy my relationship with my father for falling in love with Australia and robbing me of my heritage. Why does being born Australian now mean psychological punishment?

Come on. Enough is enough please. I have had a gutful of constant ‘acknowledgment’ “welcome’ harassment day in day out, it is destroying our lives.

KemperWA

Have you tried wearing lederhosen?

Oh no need Bron. That’s for Bavarians! My folk are from the north, or as the Bavarians like to call us, ‘Fischkopf’, translation, fish heads. See I have (could have had?) a rich cultural heritage! But alas, through no fault of my own I was born (stolen away to?) in different country, on a different continent, in a different hemisphere, speaking a different language,

In all seriousness, this is why it is very sad that Australian governments and corporations threaten Australians with these race and land declarations when it knows full well a great proportion of us have absolutely, 100%, lost our cultural connections to our ancestral indigenous homelands. I am surprised that the Aboriginal industry, all of whom have never left this hemisphere, continent, or country land, have the nerve to remind us of this every second of the day. Sad, if not embarrassing. Tell you what, I would rather be called a fish head by my brethren that a ‘white colonist’ by the ignorant activists.