Published in London in 1975 as a critique of progressive, New Age education and edited by C.B.Cox and Rhodes Boyson, the publication Black Paper 1975 The Fight for Education should be compulsory reading for anyone with an interest or involvement in education and schools. If ever there was a panacea for the dismal and substandard education system being forced on generations of British and Australian students this is it. In opposition to the faddish and dumbed-down approach dominant over the last 50 years in both countries, Black Paper presents a compelling case detailing what real education involves and the most effective way to raise standards and improve results.

The Black Paper’s authors include notables such as Kingsley Amis, Iris Murdock, G. H. Bantock and H. J. Eysenck and under the heading ‘Black Paper Basics’ the authors detail 10 points that, if implemented, would save billions of dollars wasted on proven failures and provide students with a challenging and enriching educational experience.

In opposition to the belief that children are inherently good made famous in Rousseau’s Emile and championed by A. S. Neil in his ultra-progressive, child-centred school Summerhill, point 1 states “Children are not naturally good. They need firm, tactful discipline from parents and teachers with clear standards”. Children do not learn intuitively or naturally, they have to be taught.

Point 2 acknowledges the importance of competition and meritocracy in education – instead of the prevailing ethos where all are winners and teachers are told it is wrong to rank students in terms of performance. One reason Asian students consistently outperform British and Australian students in international mathematics, science and literacy tests is because tests and examinations are a normal part of their school life and students are pressured to excel.

In both countries classroom teachers are expected to be masters of their subject as well as counsellors, mentors and guides by the side teaching everything from stranger danger, healthy eating to wellness and road safety. Teachers are also overloaded with a debilitating and time consuming assessment and reporting regime.

As an alternative Point 3 of the Black Paper argues “It is the quality of teachers that matters” and “We need high-quality, higher-paid teachers in the classroom, not as counsellors or administrators”.

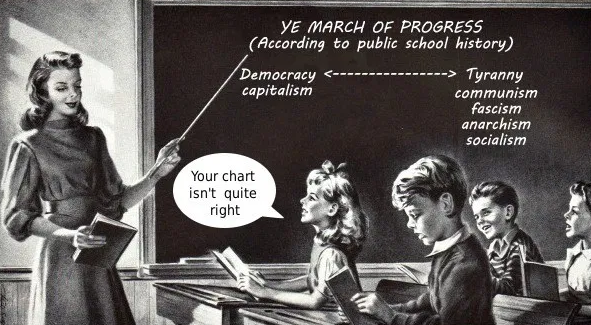

In opposition to today’s classrooms, where students are indoctrinated to be new-age, politically correct warriors in areas ranging from climate change and gender fluidity to radical feminist theory, Point 4 argues “Schools are for schooling, not social engineering”. A teacher’s duty is not to indoctrinate students but instead to teach them in a balanced and impartial way, especially in relation to controversial subjects where there are differing views and opinions. It is also wrong to use subjects like English and history as vehicles to enforce cultural-left ideology and group think.

Point 5 argues it’s vital students are numerate and literate, and the education they receive develops and extends their abilities and interests to the fullest capacity. For years now the evidence proves otherwise. Too many students enter secondary school without the basics and destined to underperform.

After observing “Every normal child should be able to read by the age of seven”, Point 6 adds the qualification that teachers must “use a structured approach” to literacy. As noted in the chapter ‘Reading Instruction in America” a structured approach refers to phonics and phonemic awareness instead of a whole language model. Whole language is based on the mistaken assumption that reading is as natural as talking and if children are immersed in a rich and varied language environment they will eventually learn to read. The research and the evidence proves otherwise, with generations of students, especially boys, destined to failure.

In addition to arguing all students are winners what currently passes as education opposes streaming and grouping students in terms of motivation and ability. In England this led to closing state-funded Grammar schools that selected students on the basis on an entry test in favour of comprehensive schools open to all.

In Australia, the Australian Education Union consistently argues against selective government schools like Melbourne High and Sydney’s Fort Street on the basis that they are elitist and unfair, as low socio-economic students are excluded. The policy of mixed-ability classes as opposed to streaming is another example of misplaced egalitarianism pervading education. Under Point 7 the Black Paper argues that, while motivated by an anti-elitist sentiment, closing Grammar schools led to even greater inequality. “Without selection the clever working-class child in a deprived area stands little chance of a real academic education,” it notes.

Working-class children are further disadvantaged, according to Point 8, as without rigorous, academically based external examinations such children “suffer when applying for jobs if they cannot bring forward proof of their worth achieved in authoritative examinations”.

Mirroring recent debates about the lack of academic freedom in universities across the Anglosphere, Point 9 argues, “Freedom of speech must be preserved in universities. Institutions which cannot maintain proper standards of open debate should be closed”.

Victoria’s one-time premier and education minister, Joan Kirner, argued schools had to be used as an instrument to bring about the socialist utopia and central to this was her mantra ‘equality of outcomes’, instead of equality of opportunity.

Ignored and, as argued by Point 10 in the Black Paper, positive discrimination, quotas for so-called victim groups and handicapping gifted students proves counterproductive as, “You can have equality or equality of opportunity; you cannot have both. Equality will mean the holding back (or the new deprivation) of the brighter children”.

An Australian equivalent to the British Black Paper was produced in 1992 by the Institute of Public Affairs’ Education Policy Unit, Educating Australians. The publication also criticises progressive education for being academically substandard and for promoting equality of outcomes instead of competition and meritocracy. Much of what students learn is condemned as “ideological, rather than educational”, and as an alternative the paper champions a liberal view of education, one committed to “the impartial pursuit of truth”, “the transmission of knowledge of major human achievements” and “the maintenance of order and discipline”.

History proves how prescient the Black Paper and Educating Australians were in warning about the dangers of implementing a dumbed-down, substandard and politically correct school curriculum.

In both countries too many students are still leaving school illiterate, innumerate and ignorant of the benefits and strengths of Western civilisation. Worse still, both major political parties when given the chance to govern in the UK and Australia have done nothing to remedy the situation.

Dr Kevin Donnelly is a senior research fellow at the Australian Catholic University and author of How Political Correctness Is Still Destroying Australia (kevindonnelly.com.au)

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search