Kind Hearts and Coronets

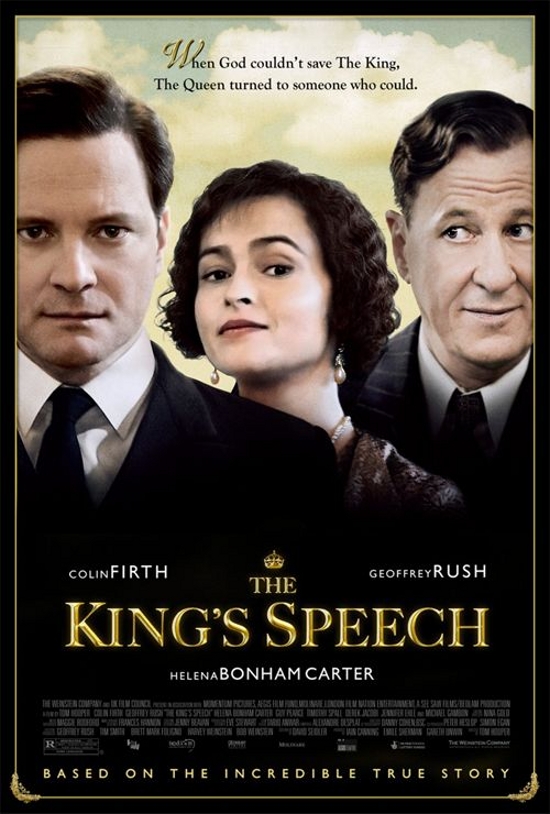

For those of you who don’t get out much, The King’s Speech is about the successful treatment of King George VI’s stammer by unorthodox but gifted speech therapist Lionel Logue, so that he could speak confidently in public and (eventually) lead his country in its darkest hour. It has an A-grade cast, but that doesn’t always guarantee a good movie: about 18 months ago I saw these same actors – Helena Bonham Carter, Timothy Spall and Michael Gambon – phoning it in for Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince. Not so in The King’s Speech: you get your money’s worth out of them, and they show what they can really do when they want to.

There are some resonances with The Madness of King George (but without huge wigs) and also The Young Victoria (with considerably less flouncing).  Having said that, The King’s Speech is certainly a far more enjoyable film than The Madness of King George, inasmuch as it does not feature straightjackets and also lays off the echt-republican sentiment. But I also found it more enjoyable than The Young Victoria because it lays off the Mills & Boon sentiment; in fact, it is a profoundly unsentimental film, and that is why half the audience were in tears when it finished. It has a marvellous balance of comedy and tragedy; the settings are glorious and yet the whole thing manages to feel realistic and uncontrived.

Having said that, The King’s Speech is certainly a far more enjoyable film than The Madness of King George, inasmuch as it does not feature straightjackets and also lays off the echt-republican sentiment. But I also found it more enjoyable than The Young Victoria because it lays off the Mills & Boon sentiment; in fact, it is a profoundly unsentimental film, and that is why half the audience were in tears when it finished. It has a marvellous balance of comedy and tragedy; the settings are glorious and yet the whole thing manages to feel realistic and uncontrived.

One of the noticeable strengths of the movie is that it captures the emotional reticence of the time – although this was noticeably under assault by the 1930s – and also the remarkably private lives led by most of the Royal Family. When the Duchess of York first comes to visit Lionel Logue, he does not recognise her, because her image has not been plastered everywhere and there is no television to record her every waking moment. A century of studied respectability had transformed the Royal Family from the taunt of eighteenth century broadsheets into a carefully guarded enclave: a firm, not a family. This, of course, is about to change, as the dreaded wireless and newspaper begins to intrude and to turn them once more into media performers.

However, The King’s Speech is not principally about Monarchy As Outdated Relic of Bygone Era. Instead, it is about a not very intelligent man carrying a heavy emotional burden, who is put in a situation beyond his capacity and to everyone’s surprise makes a really good job of it. Colin Firth as the Duke of York, later King George VI, does not look a thing like him, but this doesn’t matter in the least because he captures the complexity and private struggles of this peculiar, unloved and largely friendless man. This movie also shows what an experienced actor can do with a small role: like Jim Broadbent as William IV in The Young Victoria, Michael Gambon as George V packs a huge amount into what is really only about five minutes of screen time.

I didn’t think I’d ever say anything nice about Geoffrey Rush in a film review, but here I am doing it because he’s just perfect as Lionel Logue: kind, talented, but very aware of the precarious state of his (unqualified) practice. Rush as Logue is more Barry Humphries than Barry McKenzie; he has the inter-war educated Australian accent perfectly – half-English, only occasionally slipping into twang. I wish I could say the same for Jennifer Ehle, who is inexplicably cast as Logue’s wife Myrtle and sounds more Coronation Street than Ramsay Street.

If you groaned inwardly at the thought of Helena Bonham Carter as the Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth), don’t worry: she plays the Queen Mum as cheerful, sweet-eating, and is charming and just the teeniest bit fake with the lower classes. In other words she is exactly like the real thing, and her magnificent snubbing of Wallis Simpson (Eve Best) at a hideous Balmoral cocktail party is highly enjoyable. The movie’s real surprise is Guy Pearce as Edward VIII – selfish, freakishly emotional and fundamentally irresponsible. I think ‘David’ was not quite as hectic as Pearce makes him (I always imagine him as more like Prince Charles at his worst), but his bullying and moody snappishness is, I suspect, spot on.

And there are always the cameos: a frail-looking Derek Jacobi as Archbishop Cosmo Lang, Claire Bloom as Queen Mary, Timothy Spall as a remarkably jowly Winston Churchill, and – ladies, be warned – an old and corrugated Anthony Andrews as Stanley Baldwin. Andrews really does look as if he’s been carrying the weight of government through some anni horribili, and so when we see him resign as Prime Minister it makes perfect sense; in fact, you want to hop up and help him down off the screen and into a waiting taxi. Unkind and extremely critical persons would say that Spall was miscast as Churchill, and that Andrews lets the pouches under his eyes do most of the acting (like Spall’s jowls), but if you want to go to the movies with someone like that, then that’s up to you.

But regardless of who you go with, do go and see this movie. Really, do go. Director Tom Hooper deserves the royalties, no pun intended, and if we all pony up, he might make more movies like this. It’s quite superb, and easily one of the best movies made in the last ten years, and it richly deserves to win everything thrown at it.

The King’s Speech – trailer:

King George VI

The real King’s Speech:

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search