At 4.15 on the morning of Monday, 24 May 1819 in the south-east wing of Kensington Palace, a daughter was born to Edward, Duke of Kent, the 51-year-old fourth son of George III, and Mary Louisa (Victoria), fourth daughter of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Saalfeld and widow of the reigning prince of Leiningen. There had been a rush to the altar of the three unmarried sons of the King following the death in childbirth of the Prince Regent’s only child, Princess Charlotte. As Edward’s older brother William, Duke of Clarence had also recently wed, there was no certainty that Edward’s daughter would be queen. It had been a rocky journey from Leiningen to London and even the christening was fraught. The infant’s godfather, George, the Prince Regent, refused her mother’s choice, Victoire Georgiana Alexandrina; but finally agreed to Alexandrina Victoria after her other godfather, the Tsar, and her mother.

At the time of her birth, apart from that Tsar, Alexander I, the most powerful monarch in Europe, Frederick William III ruled Prussia; Francis I was Emperor of Austria, formerly the last Holy Roman Emperor (thus the Doppelkaiser – double emperor); while Louis XVIII reigned in France, four years after the final defeat of Napoléon languishing by then in exile on St Helena.

In Italy that month Keats was writing La Belle Dame sans Merci and most of his major odes: Ode to Psyche, Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale, Ode on Indolence and Ode on Melancholy; while in Ravenna, Byron was in the midst of an affair with the newly married Teresa, Contessa Guiccioli, penning the first five cantos of Don Juan.

Meanwhile, Lachlan Macquarie was in his tenth year as Governor of New South Wales and unaware that Lord Bathurst, the Colonial Secretary, had commissioned John Bigge to investigate and report on the Scottish soldier’s administration and the future of the penal colony. By September 1819, Bigge had arrived in Sydney. William Sorell as Lieutenant Governor, was bringing some order to Van Dieman’s Land, while it would be another fifteen years before the Henty brothers settled at Portland and made the Port Philip District, as present-day Victoria was then known, as a place for a settlement.

In January 1820, the Duke of Kent died unexpectedly and within a week his mad old father, George III, was also dead. Victoria was now third in line to the throne. Strangely, it was not until she was eleven that she was told she was likely to be Queen. The Duchess of Kent and the ambitious, mendacious comptroller of her household, the Irish baronet Sir John Conroy, ensured that the young princess was subject to no other influences and she endured an isolated childhood

Eventually, when, on the death of her fond, old sailor uncle, William IV, in June 1837, the 18-year-old Victoria became Queen, she banished Conroy and distanced her mother. She worshiped her first Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne (played with dash and wit by Rufus Sewell in the current eponymous ITV series). ‘Lord M’ taught her much, and was only replaced when she wed her first cousin (her mother’s nephew), Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in 1840. Although he had to wait seventeen years for the official title, Albert was quite soon, but never quite, co-sovereign, his icy rationality balanced her fiery temperament and, even after his devastating death in 1861, he exercised an extraordinary influence on the family, the court, the country and the empire.

Increasingly plump and wreathed perpetually in black crepe, she reigned alone for another four decades, as Queen of an empire, she was already, in reality, an Empress but by January 1, 1877, her doting Grand Vizier, Disraeli, officially fixed for her the title ‘Empress of India’.

What is intriguing — it appears to have been a subject so far unexamined by biographers — is Victoria’s personal links, within this vast empire, to Australia. Unlike India, we had no Munshi. Despite being head of an empire on which the sun never set, the Queen never travelled north of Golspie, southwest of San Sebastián, southeast of Florence or east of Berlin. The only part of her Empire she did visit was Ireland.

As historian Sir David Cannadine observed in his beautifully-written study of the Empire, Ornamentalism, while the Great Queen relished Disraeli’s transformation of her into “the imagined heir to the Mughal emperors, in other respects she played a limited and sometimes resistant role in the cultivation of the imperial image.” She frequently wrote to her prime ministers colonial secretaries and governors voicing her approval or disapproval (often unsolicited) of colonial policies. Charles Reed in his Royal Tourists, Colonial Subjects and the Making of a British World 1860 – 1911 (University of Manchester Press, 2016) estimated that the Queen wrote an average of 2500 words every day of her adult life. Yet while she even adopted a Maori child as her godson after his parents, a Ngapuhi chief and his wife, lamented the death of Albert, she repeatedly rejected proposals from her colonial subjects for a royal visit, insisting that family and the monarchy’s duties at home came first.

As historian Sir David Cannadine observed in his beautifully-written study of the Empire, Ornamentalism, while the Great Queen relished Disraeli’s transformation of her into “the imagined heir to the Mughal emperors, in other respects she played a limited and sometimes resistant role in the cultivation of the imperial image.” She frequently wrote to her prime ministers colonial secretaries and governors voicing her approval or disapproval (often unsolicited) of colonial policies. Charles Reed in his Royal Tourists, Colonial Subjects and the Making of a British World 1860 – 1911 (University of Manchester Press, 2016) estimated that the Queen wrote an average of 2500 words every day of her adult life. Yet while she even adopted a Maori child as her godson after his parents, a Ngapuhi chief and his wife, lamented the death of Albert, she repeatedly rejected proposals from her colonial subjects for a royal visit, insisting that family and the monarchy’s duties at home came first.

Victoria and Albert’s second son, ‘Affie’ (Alfred, later, to us, Duke of Edinburgh) was the closest Australia got to an encounter with the Queen. Albert had sent him off to sea at 14, much to his mother’s distress. She wrote to her daughter, Vicky (Crown Princess Frederick of Prussia to us) “…. he was taken away … by Papa is most cruel upon the subject. I assure you, it is much better to have no children than to have them only to give up!” In the event, Professor Rees claims that Affie “would be seen in the flesh by more people in the colonial empire than any other royal before the advent of the jet age.”

In 1867-1868, 23-year-old Alfred spent eight months in Australia (pictured above with Ballarat miners in 1867). Manning Clark rather sourly condemned him for hunting and whoring his way through the country. Nevertheless, he proved a popular visitor and provoked widespread sympathy when he was shot by a mad Fenian at Clontarf. Alfred appealed in vain for clemency and amidst a mood of imperial outrage, Henry O’Farrell (at right) was executed. It was thirteen years before another royal visit — Albert Victor and George, teenage sailors like Uncle Affie, and the first and second sons of Bertie, Prince of Wales. The next royal visit was not until 1901. George, by then Duke of York and heir to his father, had been lobbying since 1897 to visit Australia and New Zealand.

In 1867-1868, 23-year-old Alfred spent eight months in Australia (pictured above with Ballarat miners in 1867). Manning Clark rather sourly condemned him for hunting and whoring his way through the country. Nevertheless, he proved a popular visitor and provoked widespread sympathy when he was shot by a mad Fenian at Clontarf. Alfred appealed in vain for clemency and amidst a mood of imperial outrage, Henry O’Farrell (at right) was executed. It was thirteen years before another royal visit — Albert Victor and George, teenage sailors like Uncle Affie, and the first and second sons of Bertie, Prince of Wales. The next royal visit was not until 1901. George, by then Duke of York and heir to his father, had been lobbying since 1897 to visit Australia and New Zealand.

If Victoria would not come to her people, some would go to her, and more easily accessible records show that a number of Australians were received by their sovereign in the best possible circumstances: to be honoured. As Professor Cannadine aptly put it, “Hierarchy, it bears repeating, homogenised the heterogeneity of empire. Indeed, there were important ways in which, from within the metropolis, the vision of empire was encouraged and promoted, so to make it more coherent and convincing. One such means was by the expansion and codification of the honours system.” Lord Elgin noted, “in the colonies, premiers and chief justices fight for stars and ribbons like little boys for toys, and scream at us if we stop them.”

The trusty Australian Dictionary of Biography records a few occasions where Australian-born politicians were personally invested by the Queen. In 1887, while at an Imperial Conference, Alec’s father/Alexander’s grandfather/Georgina’s great-grandfather, John William Downer, was delighted to find he was to be knighted personally by Victoria. The ANU School of History’s Dr Karen Fox has uncovered the case of George Dibbs, a republican and reluctant knight and thrice Premier of New South Wales, who succumbed to the Queen’s insistence of knighting him by her own hand. And, finally, Edward Witernoon, Western Australia’s agent-general in London from 1898-1901, had the honour, at Osbourne in 1900, of being the last person to receive a KCMG from Queen Victoria.

The Queen’s handsomely honoured colonial governors — most of them earlier or later held positions at Court — were not, of course, Australian but they had more opportunity to share their views and impressions of their terms as her representative. Lords Jersey, Carrington, Lamington and Hopetoun were among them.

Michael Davie, onetime editor of The Age and of Evelyn Waugh’s engrossing and revealing diaries, gives a lively account in his book, Anglo-Australian Attitudes (Secker & Warburg, 2000) of a particularly fascinating viceroy, William Lygon (at right), 7th Earl Beauchamp. At the astonishing age of 29 he was appointed Governor of New South Wales. Eventually, despite being the father of seven and leader of the Liberal Party in the Lords, he was undone by his fondness for his valet and fled to the Continent in disgrace, becoming Waugh’s inspiration for Lord Marchmain. Well-born, rich and an exemplar of correct form (as a father he would address his own children as Lord Elmley, Lady Lettice, Lady Sybil), he seemed to the Colonial Secretary, that wily old imperialist Joseph Chamberlain, to possess the right stuff. Before he left for Sydney, claiming he knew nothing of the colony he was to govern, he was called to Windsor to receive the KCMG. After arising as Sir William, he joined Her Majesty for dinner where the ‘conversation was subdued’. Beauchamp noted too that the Queen never sat next to a stranger. ‘Having thought of her anxiety to be called Empress of India, I expressed some hope that Her Majesty should honour the various colonies by assuming some such as Empress of India, Canada and Australia’. To this initiative the Queen made no response, but instead, ‘complained of a lack of good modern hymns and prayers.’

Michael Davie, onetime editor of The Age and of Evelyn Waugh’s engrossing and revealing diaries, gives a lively account in his book, Anglo-Australian Attitudes (Secker & Warburg, 2000) of a particularly fascinating viceroy, William Lygon (at right), 7th Earl Beauchamp. At the astonishing age of 29 he was appointed Governor of New South Wales. Eventually, despite being the father of seven and leader of the Liberal Party in the Lords, he was undone by his fondness for his valet and fled to the Continent in disgrace, becoming Waugh’s inspiration for Lord Marchmain. Well-born, rich and an exemplar of correct form (as a father he would address his own children as Lord Elmley, Lady Lettice, Lady Sybil), he seemed to the Colonial Secretary, that wily old imperialist Joseph Chamberlain, to possess the right stuff. Before he left for Sydney, claiming he knew nothing of the colony he was to govern, he was called to Windsor to receive the KCMG. After arising as Sir William, he joined Her Majesty for dinner where the ‘conversation was subdued’. Beauchamp noted too that the Queen never sat next to a stranger. ‘Having thought of her anxiety to be called Empress of India, I expressed some hope that Her Majesty should honour the various colonies by assuming some such as Empress of India, Canada and Australia’. To this initiative the Queen made no response, but instead, ‘complained of a lack of good modern hymns and prayers.’

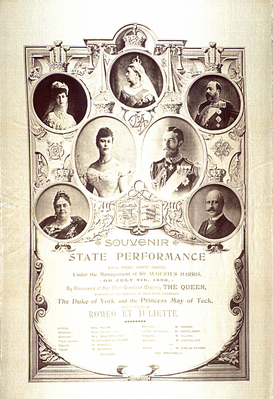

A favourite account of an encounter with the Queen was when she commanded the presence — and voice — of the redoubtable Nellie Melba. On July 4, 1890, our Richmond-born diva travelled to Windsor by train with Jean and Edouard de Reske and Jean Lassalle. As Ann Blainey describes in her irresistible biography, I Am Melba, the concert was scheduled for 4pm, but it did not start until 5 pm because they were waiting for the Queen’s daughter, Vicky (by now, to us, the Empress Frederick of Prussia), who had gone out driving and not yet returned. Melba sang, among other things, Caro Nome, the waltz from Romeo and Juliet, and a duet from Traviata with Jean de Reske. (the program for ‘Romeo and Juliet’ at left). They concluded with the last act from Faust sung by Melba and the de Reske brothers. Then the (younger) Empress arrived and the Queen asked Melba to repeat some of her arias for Vicky. Rushing back to perform in Rigoletto, Melba made it to Covent Garden as the curtain went up. A grateful monarch presented Melba with a souvenir brooch for her trouble.

A favourite account of an encounter with the Queen was when she commanded the presence — and voice — of the redoubtable Nellie Melba. On July 4, 1890, our Richmond-born diva travelled to Windsor by train with Jean and Edouard de Reske and Jean Lassalle. As Ann Blainey describes in her irresistible biography, I Am Melba, the concert was scheduled for 4pm, but it did not start until 5 pm because they were waiting for the Queen’s daughter, Vicky (by now, to us, the Empress Frederick of Prussia), who had gone out driving and not yet returned. Melba sang, among other things, Caro Nome, the waltz from Romeo and Juliet, and a duet from Traviata with Jean de Reske. (the program for ‘Romeo and Juliet’ at left). They concluded with the last act from Faust sung by Melba and the de Reske brothers. Then the (younger) Empress arrived and the Queen asked Melba to repeat some of her arias for Vicky. Rushing back to perform in Rigoletto, Melba made it to Covent Garden as the curtain went up. A grateful monarch presented Melba with a souvenir brooch for her trouble.

The Queen Empress would live just three weeks after Federation. The Great White Queen finally joined her adored Albert on January 22, 1901. Georgie (soon, for us, the Prince of Wales) was there. Grandmama had fought his going until a few months before she died. She had even resisted the concept of the Commonwealth of Australia, too reminiscent of the dreadful Cromwell.

It was a remarkable life. While two of our states were to bear Her Majesty’s name, and statues, squares, suburbs, streets and institutions still pay homage to her reign, Victoria remains a potent but distant force.

Mark McGinness lives in the United Arab Emirates. He wrote most recently on the ascent to the Chrysanthemum Throne of the Emperor Naruhito

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search