How many of us were in my Willagee branch of the Communist Party in Perth around 1960? Maybe six or eight. We bonded well but we weren’t powerhouses of the intellect. We’d gloat about the impending world revolution, nut out ways to get it started, and then pivot to the contentious stuff – whose turn was it to letterbox Garling Street?

I can now assume one of our tight-knit band was an ASIO informer. From 1956 ASIO’s Operation Sparrow aimed to put an agent into every Communist Party branch. The best-known informer is Phil Geri, who kept reporting on the Ballarat branch while its membership declined to four (or maybe five, Geri included).

My mother and stepfather, who did high-level CPA work, were confident that Party vigilance screened out would-be informers. “I can spot one a mile off,” my stepfather would say, with a sardonic grin. In reality ASIO riddled the Party with spies, probably to Central Committee level. Once in, they were seldom outed because the Party never thought to check: Who volunteers for dreary tasks? And who pays their Party dues on time? Tick the two boxes and there’s your ASIO agent.

My favorite historian is Professor Phil Deery of Victoria University. He specialises in ASIO-CPA relations and refreshes my memories of a politically mis-spent youth. I stumbled across his latest revelations about ASIO’s Adelaide spy, Anne Neill, in Labor History (11/2018), “A Most Important Cadre”: The Infiltration of the Communist Party of Australia during the Early Cold War. Deery’s stuff is too good to lie unread in Labor History, hence I’m giving it an audience here. Thank Deery, not me.

For reasons unexplained, ASIO released 13 files on Anne Neill totalling 2,664 pages, with various redactions. Deery could hardly believe his luck: “On no other agent has anything like this occurred,” he writes. (There’s several pages about Neill in David Horner’s official ASIO history, published in 2014, but it’s rather mundane).

Deery’s tale is about middle-class, religious and patriotic Adelaide widow Anne Neill. From 1950-58 she was a trusted and hard-working secretary and aide to the Party leaders, slipping an extra carbon sheet into her typewriter roller and embracing what her sister disparaged as “a life of deceit”.

She almost wore out Rod Allanson, the agent-runner in ASIO’s Adelaide office, a tough character who had survived the Thai-Burma railroad. In 1950 he had slotted her into an unpaid typist job for Elliott Johnston, a top SA and federal Communist who also ran the SA Peace Council front.

Johnston eventually gained some respectability as a Supreme Court Judge and a Royal Commissioner into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (1987). It is normal for Communists to become judges, although I was somehow overlooked. War-time waterfront slacker and Trotskyite Ken Gee (aka “Comrade Roberts”) later graced the bench of the NSW District Court for a decade.

Anne Neill’s career and my own do have some eerie parallels.[1] Her first undercover job was to help run the Stockholm Peace Appeal of 1950 to ban atom bombs. Like Neill I gathered signatures, corrupting ten-year-old playmates at Nedlands Primary School. Neill and I helped generate the purported Australian tally of 200,000 signatures, which in turn helped generate the purported 475m signatures worldwide. That was one in every 40 Australians and one in every five humans in the world. Stalin knew how to get things done.

Two years later, Neill caught the train from Adelaide to represent SA at Sydney’s Youth Carnival for Peace & Friendship. I did the same from Perth at 12, as WA’s youngest delegate, raising high the banner of the Junior Eureka Youth League.

Neill slaved over costumes for the Communists’ New Theatre production of the Reedy River musical – it must have toured to Perth, as I can still hum, “Ten miles down Reedy River one Sunday afternoon/I rode with Mary Campbell to that broad, bright lagoon…”

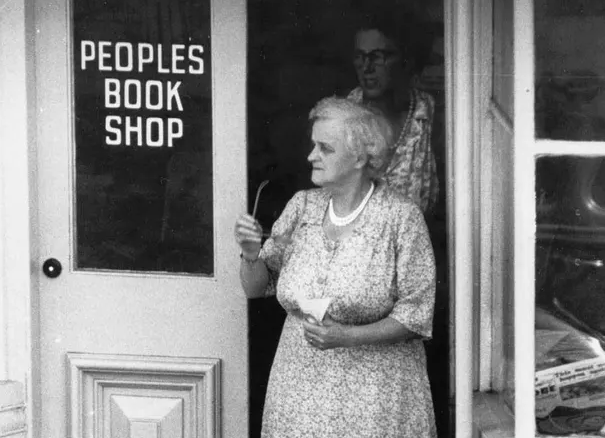

That’s enough about me. A surveillance photo of Neill in the doorway of Adelaide’s “People’s Book Shop” (above) shows a dumpy woman about 50 with flimsy white hair, thin lips, a strong jaw and a determined expression. Her main concession to femininity is a whitish necklace topping her baggy cotton dress.

As one Party person put it, “Comrade Anne – it beats me how she gets through all the work she does. She makes costumes for the opera, is in charge of costumes for the New Theatre, makes jars of pickles and marmalades for Party fairs, as well as writes letters and is Secretary of other organisations.”[2]

By late 1952 ASIO was calling her its “most prolific source”, as she supplied a succession of three agent-runners with hundreds of reports rated highest-grade. One case officer noted that her morale was “surprisingly high” and that she was an “absolute inspiration”.

ASIO’s Allanson recalled, “Anne Neill was so active that she demanded much of my time and attention. And when I had finished my normal day’s work, I found it necessary to have clandestine meetings with her, night after night, so that I could record all the detail she provided and also brief her on further action required.”

She was raised a devout Christian by conservative and imperial-minded parents and took on her spy role as a responsible citizen keeping track of subversives as a duty to her country and the Crown. She tracked not only the Party and the Peace Council, but at least seven other Communist fronts such as the Union of Australian Women and Realist Writers’ Group. At times she would be at their meetings seven nights a week.

She fooled the Party largely because she looked so guileless –“the middle-aged lady with the beautiful, innocent blue eyes”, as one Party wife recollected. SA Party boss John Sendy found her “well-mannered, unassuming and quite charming” but after she was outed, he modified his assessment: “a b….. [sic] old bitch – she was so nice all the time.”

So nice she didn’t have to worm her way into the Party, having been told the Party “would be pleased to welcome you”. This slack security was when the Party was under siege by Menzies and notwithstanding Neill’s previous overt membership of the Liberal & Country League! The Melbourne Herald later called her “a white-haired widow with a kind face. She could be the woman from the house across the corner.”

After the Sydney Peace Carnival, she wangled her way onto a deputation to another “Peace Conference” in Peking. She loaded the dice by saying she could pay her own fares, thanks to a £400 insurance payout which in fact was ASIO money.[3] En route she wrote letters to her family disclosing ASIO secrets, which alarmed ASIO when it opened them. The Catholic News-Weekly even quoted one of her travelling companions saying Neill was unsympathetic to Communism – luckily for ASIO, Party leaders didn’t read News-Weekly.

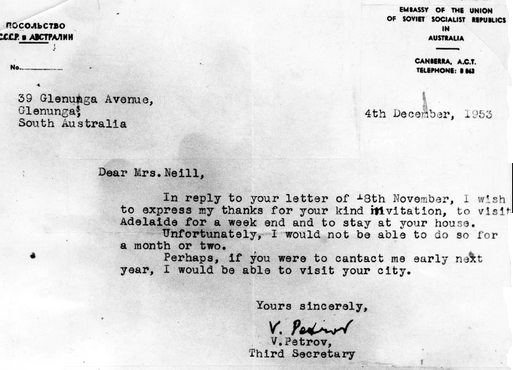

When she blabbed to the Australian Trade Commissioner in Hong Kong that she was a secret agent, he thought her claim ”outrageous”. But she came home with a swag of materials for ASIO on Communist policies, issues and personalities. The Party was just as delighted with their delegate and she was lionised on lecture tours, enthralling the faithful with 90-minute inspirations. Indeed, her status was so high that the Soviet Embassy in November 1953 gave her a half-hour private audience with Vladimir Petrov. He and wife, Evdokia, deferred her invitation to stay with her in Adelaide. Her hob-nobbing backfired when the Petrovs defected in April 1954: Party bigwigs wrongly suspected she had a hand in it.

Neill, in the light-coloured coat, visits Moscow.

Without warning they interrogated her twice within two days, probing for holes in her ASIO-provided cover stories. They particularly demanded documents to authenticate her (ASIO-sourced) £400 windfall. While she stalled for time, ASIO alerted her solicitor and another friend to lie about this money if required. Ever scrupulous, ASIO added a marginal note to “make sure this matter is fully insulated so that there is no possible chance of perjury.”

Using considerable psychological skills, ASIO briefed her to “Threaten to resign from the CP of A and frontal organisations, and indicate indignation at the continual questioning.” Her inquisitor, Elliott Johnston, fell for this ruse, soothing her, “Now, don’t be upset, don’t get angry, all I want is that written paper to prove where you got that money”. The CPA State Secretary, Eddie Robertson, feared she might tell the Party to “get f—” if they pushed her too hard.

Deery writes that Neill’s health deteriorated. “Within two days, she had undergone a two-hour grilling, a three-hour briefing with ASIO officers, a long meeting/dinner with Marjorie Johnston (Elliott’s wife) that Neill apparently recorded, and the interrogation by the CPA Control Commission.” The historian attributes her success to “calm steadfastness in the face of interrogation, the careful handling and shrewd advice by her case officer, and the stonewalling of repeated requests to supply documentary proof.”

After a considerable sick spell, she returned to the Party fold and resumed her mind-boggling industriousness, working long hours on costume-making for June’s production of Reedy River. Party leaders promoted her to delegate to the State Conference and she spoofed them for a further four years. By mid-1958, however, eight years late, suspicions arose. It was likely through Party women’s intuition rather than male Party intellect. A female ASIO agent discovered from the mother of CPA boss John Sendy that Neill had been too darn curious about too many Party issues, and the documents about the £400 had, after all, never been produced. Mrs Sendy said Neill was

In everything … [She] goes about getting information from people and she is so charming and so nice about it … She gets paid to do it. Actually, I hate mentioning the word, but it is Security … She was put on to me by Security. She must know that I spoke to John about it … I did have my suspicions when she came here to pump me [about John Sendy, when he attended a training school in China] … John said, “Look, Mum, there is nothing we can do at present … [but] we will hold her back from getting in too far.” We know she only gets a widow’s pension, yet she can have a trip abroad … I couldn’t do it. How does she do it? She is always ready to pay her payments to the Party. She will give anything to the Party. You or I couldn’t do it … We are watching her closely now. John has suspected her for some time, but it is only recently that he told me that he was now fairly certain about it. The Party had “tried all ways to trap her but we couldn’t” and her house was watched for 14 days and nights, “but she wasn’t seen.

By this time Neill was religiously involved in the Commonwealth Revival Crusade and boring her case officer with tales about godly revenge on Russia and faith-healing miracles by American evangelist Billy Adams.

Both the CPA and ASIO were happy to see her eased quietly out of Party work. It left quite a gap, as Adelaide by then had fewer than 20 members. ASIO presented her with a pricey cutlery set as a memento. But with her visceral hatred of Communists she spent another three years writing to order scores of highly personal “character studies” of Party figures, up to eight typed pages long. She also rejoined the Liberal & Country League.

In December 1961, in a bizarre denoument, she went public in Adelaide’s Daily Mail with tell-all features about her ASIO career, under headings like “Secret Service Housewife”, “I Spied for Security”, “I Join the Party”;, “I Go Behind the Iron Curtain”; and “I Talked Alone to Petrov”. Sub-headings included “How she tricked the Reds” and “Mixed with top men in Kremlin.” The pieces were to be syndicated before the December 1961 election but Sunday Mail editor K.V. Parish held them over until after the election. Menzies scraped home with a one-seat majority. Deery doesn’t comment on whether Parish’s decision was good or bad form.

In December 1961, in a bizarre denoument, she went public in Adelaide’s Daily Mail with tell-all features about her ASIO career, under headings like “Secret Service Housewife”, “I Spied for Security”, “I Join the Party”;, “I Go Behind the Iron Curtain”; and “I Talked Alone to Petrov”. Sub-headings included “How she tricked the Reds” and “Mixed with top men in Kremlin.” The pieces were to be syndicated before the December 1961 election but Sunday Mail editor K.V. Parish held them over until after the election. Menzies scraped home with a one-seat majority. Deery doesn’t comment on whether Parish’s decision was good or bad form.

Neill’s revelations left the Party with an emu egg omelet on its face. ASIO taps recorded bigwigs now calling their Stakhanovite ex-worker a police pimp, traitor, provocateur and shameless stool pigeon. “Personally,” stated one Party leader Alan Miller, “I would rather hang myself than do what she has done.” Another, Graham Beinke, thought, “It is a pity she is old because by the time Communism comes to Australia she will be dead and we won’t be able to do anything to her.” There were suggestions of retaliation ranging from psychological pressure to physical violence. These were quickly suppressed by Party leaders, who adopted a wait-and-see policy, Deery writes.

She went on a TV panel but gave rambling answers and factual slips. ASIO was discomfited and for next time, considered that “a prior approach should be made to a trusted, loyal and discreet member of the interviewing panel.”

Menzies praised her work and her decision to publish the articles, saying that she’d done a “good service” to Australia because she awakened people to the role of “innocent-looking communist ‘front’ organisations”.

Neill next became a celebrity of the far-right fringe, such as Eric Butler’s luridly anti-Semitic League of Rights. She became a Holocaust denier (“Only propaganda – Jewish lies”) and Protocols of the Elders of Zion truther. She even alleged that a Zionist was calling the shots top-level within ASIO. Her late years devolved into fantasies about Russian spies and retributions and she went into care in 1980 at age 81.

Deery hedges his bets on whether Neill’s unmasking of CPA plots had any point. It depends on whether the “peace movement” was genuinely subversive or merely political, he says. In 1977, Royal Commissioner Robert Hope defined “subversion” to include criminality, severely cramping ASIO’s style.

Retrofitting the “criminality” definition, Deery says little in those many hundreds of Neill’s assiduous reports could be regarded as “subversive.” With CPA membership in SA totaling only 220 in 1953, Neill and ASIO were tilting at windmills. “Threats to national security from Communist subversion may have existed elsewhere, but not from South Australia in the 1950s,” he concludes.

One day ASIO’s cutlery gift to Anne will turn up on Antique Roadshow. I’m putting in a bid.

Tony Thomas’s hilarious history, The West: An insider’s tale – A romping reporter in Perth’s innocent ’60s is available from Boffins Books, Perth, the Royal WA Historical Society (Nedlands) and online here

[1] The parallels weren’t really ‘eerie’ but we journalists always add ‘eerie’ to ‘parallels’. It’s like all our contrasts being ‘stark’ ones.

[2] This 1958 quote was recorded by an ASIO agent at a meeting who was unaware that Neill was also an ASIO agent.

[3] The Australian delegation of five was led by Dr John Burton, ex-secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs, known as the Labor Party’s ‘pink eminence’.

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search