Rosalind Morrison (above), chatelaine of Madresfield Court, who died on October 16, aged 74, was the last of the Lygons, rescuing the house from decline and the family name from scandal. This red-brick moated manor house usually shrouded in summer mist or winter fog sits in 4,000-acres at the foot of the Malvern Hills in Worcestershire and is approached by four tree-lined avenues – of oak, poplar, lime and cedar. Lady Morrison was the 28th generation to have lived at Madresfield since 1196. This was the house and family in the 1930s that inspired Evelyn Waugh and Brideshead Revisited. It was also the house chosen as a safe one for George VI and his family in the 1940s in the event of invasion. Charles II is supposed to have stayed there during the Battle of Worcester in 1651; but that was a war the Royals lost.

The iconic Granada Brideshead television series in 1981 and the more recent film in 2008 have inevitably linked Brideshead with Vanbrugh’s majestically baroque Castle Howard in Yorkshire. While Castle Howard may have informed Brideshead’s grey-gold hue and dome, the novel’s art nouveau chapel is a replica of Madresfield (below), where the family assembled for daily prayers. It formed the heart of the book and shaped the memorable characters that people the novel. The chapel, commissioned from Birmingham artists and craftsmen in 1902, is regarded as the most complete, and perhaps the loveliest of all British Arts and Crafts achievements.

A key figure, and Waugh’s model for Lord Marchmain, was Rosalind’s grandfather, William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp (right). The Lygons’ earldom dated from 1815. Before that, according to Jane Mulvagh’s Madresfield (2008), “The Lygons did not fly too high” – landed squires perched between merchants and gentry. But in 1899, the 7th earl was sent out to Sydney by Joseph Chamberlain as 20th Governor of New South Wales. As he was only 27 at the time, this showed either Chamberlain’s great faith in young Beauchamp or little regard for New South Wales. As he admitted “[I] scarcely knew where the colony was and certainly nothing about it.” Queen Victoria mischievously expressed the hope that a sensible nurse would accompany the boy. Instead, his sister, Mary, acted as his consort for some of his term. This Lady Mary, a vigorous supporter of local music, is generally regarded as having inspired the Enigma Variations, its composer, Edward Elgar, having frequented Madresfield since he was ten when his father tuned the family’s grand pianos and spinets. In fact, the thirteenth variation records Mary’s jou rney to Australia. Brother and sister set off on the SS Rome with a retinue of 14 and more than 100 crates of furniture, antiques, pictures and objets d’art.

rney to Australia. Brother and sister set off on the SS Rome with a retinue of 14 and more than 100 crates of furniture, antiques, pictures and objets d’art.

The ADB gives a typically neat account of Beauchamp’s time in Sydney. At Cobar, in September 1899, he offended French colonists by condemning the Dreyfus trial. Cartoonists made Beecham’s Pills jokes. His attendance at the dedication of St Mary’s Cathedral antagonized the Evangelical Council. A man of contradictions — a pompous progressive; a grandly formal Liberal — silk-stockinged, gold-braided and plumed, he op ened up Government House, Sydney, to people of the state, rather like the Buckingham Palace garden parties of today. He also befriended, and funded, Henry Lawson. As Federation loomed and Premier Sir Frederick Lyne sought a more seasoned figure as Governor, Beauchamp only served eighteen months of his three-year term. But he remained fond of the city and would return to Sydney three times in the thirties.

ened up Government House, Sydney, to people of the state, rather like the Buckingham Palace garden parties of today. He also befriended, and funded, Henry Lawson. As Federation loomed and Premier Sir Frederick Lyne sought a more seasoned figure as Governor, Beauchamp only served eighteen months of his three-year term. But he remained fond of the city and would return to Sydney three times in the thirties.

Back in England, he married Lady Lettice Grosvenor (left), sister of Europe’s richest man, ‘Bendor’, the 2nd Duke of Westminster in 1902. They had three sons and four daughters, whom their father would formally address as “Lord Elmley” and “The Lady Dorothy…..” as he graced the dinner table in his Garter riband. He sounded like a foghorn so the children called him “Boom”, though not to his face. The Lygons had a childhood of unimaginable luxury, moving, with their immediate entourage by private train between Madresfield, Halkin House in Belgrave Square, and Walmer Castle in Kent, the earl’s official residence as warden of the Cinque Ports. He bore the sword of state at the coronation of George V, became lord lieutenant of Gloucestershire, served as lord steward of the royal household, and, from 1924 to 1931, was leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords. A high and happy point in their lives was Elmley’s coming-of-age party at Madresfield, beautifully captured by William Ranken in his portrait of the family (below) in 1925.

To his children — conceived, usually, following “a delicious afternoon on my sofa”, according to his wife’s diary — he was a devoted father. However, delicious afternoons were also enjoyed with others. During his time in Sydney, The Australian Star had noted, “Lord Beauchamp deserves great credit for his taste in footmen”. Guests at Madresfield recalled the clunk of his footmen’s bracelets as they served dinner. When a guest asked Harold Nicolson, “Did I hear Beauchamp whisper to the butler, ‘Je t’adore’?” Nicolson apparently replied, “Nonsense; he said, ‘Shut the door.’”

In 1931, having commissioned a report of assignations in the library, the chauffeurs’ room, even the garage, of Halkin House, Bendor, who despised his brother-in-law (at left in fancy dress), denounced Beauchamp as homosexual and demanded his arrest. Citing ill health, Beauchamp resigned all his positions and went into exile. The Duke wrote to him, “Dear Bugger-in-law, you got what you deserved.” George V is said to have remarked, “I thought men like that shot themselves.” (H.M. meant Beauchamp) The beautiful Mary (right) – Maimie’s – romance with Prince George, the King’s fourth son, was immediately ended.

His bewildered Countess (“Bendor says Beauchamp is a bugler”) suffered a nervous collapse, and took her youngest child, Richard, with her, leaving the house to her five grown-up, unwed children. They sided with their beloved father and spurned their mother.

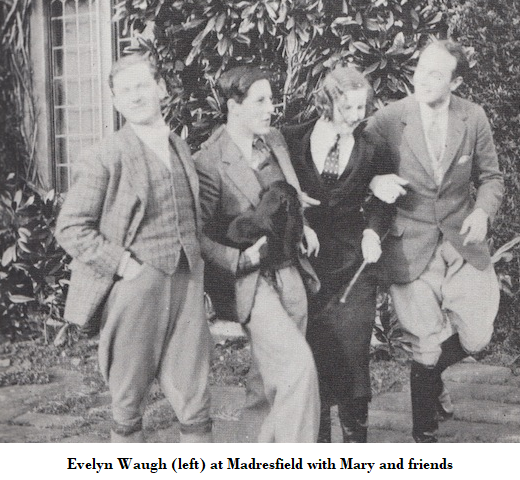

In December 1931, six months after her father’s banishment, Dorothy invited Waugh to Madresfield. As Paula Byrne’s Mad World (2010) relates, they had already inspired a great comic set piece for Vile Bodies. The Lady Sibell and The Lady Mary had been to a party in their white Norman Hartnell dresses but when they returned to Belgrave Square, they found themselves locked out and the night footman asleep. So they made their way to family friends at 10 Downing Street. The night porter woke the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, who emerged in striped pyjamas, to be greeted by the Lygon girls seeking a bed. In the morning the prime minister rang their father to ask if he would send a maid round with day clothes for the girls. “Balderdash and poppycock!” Beauchamp retorted and made them walk home in full evening dress.

Waugh fell in love with the family and spent much time there in the early thirties between his novels, travels and two marriages. In fact, he wrote much of Black Mischief there and dedicated it to Dorothy (Coote) and Maimie. In the absence of an older generation, Madresfield became a centre of jokes and fun. They called home ‘Mad’. Mad also inspired Hetton Abbey, the setting for A Handful of Dust (1934), which Waugh later wrote, should have been dedicated to Hugh, Beauchamp’s second son and favourite child.

Both Dorothy and Waugh’s brother, Alec, agreed that it was the Lygons’ situation rather than their characters which he absorbed when writing Brideshead Revisited a decade later. Like Lord Marchmain, Lord Beauchamp spent most of the rest of his life abroad, returning to Madresfield, like Marchmain to Brideshead, for only the last two years of his life. He had time to throw a bust of his countess into the moat and to whitewash her image from the chapel walls. But unlike Lord Marchmain, he made no deathbed reconciliation. Instead, his last words were apparently “Must we dine with the Elmleys tonight?”

Sebastian Flyte was thought to be an amalgam of Alastair Graham, for Waugh “the friend of his heart” at Oxford, and Hugh Lygon. Mamie Lygon (“a flawless Florentine quattrocento beauty”) clearly contributed to the portrait of Julia Flyte, her plain but enchanting sister Dorothy is a near match for Cordelia, and Elmley bears a striking and not altogether complimentary resemblance to Lord Brideshead. Lord Marchmain’s disgrace and exile (“the last, historic, authentic case of someone being hounded out of society”, as Anthony Blanche puts it) is based on that of Lord Beauchamp, though made heterosexual. Lady Marchmain’s fervour and froideur owe something to the Countess.

She died in July 1936, aged 59, and poor, alcoholic Hugh three weeks later, after falling out of a car in Germany. A distraught Beauchamp returned quietly to Madresfield for Hugh’s funeral and died two years later (in New York). Sibell, Maimie and Coote left the house as Elmley became the 8th and last Earl, and he and his older, widowed Danish wife, Mona (but glamorous; No Mrs Muspratt she), took over Madresfield.

The unhappy youngest son, Dickie, married Patricia Norman, a vicar’s daughter, in 1939. Rosalind was born on 13 October 1946 and grew up on another Lygon property, Pyndar House in Worcestershire, with her elder sister, another Lettice. In 1967, Rosalind married Gerald Ward, both were close friends of the Prince of Wales. Gerald was a soldier, banker, businessman and farmed in Berkshire. They had two daughters, Sarah and Lucy, and divorced in 1976. In 1984, Gerald became godfather to Prince Harry and in 1987 an Extra Equerry to Prince Charles.

In 1984, both Wards remarried; Rosalind to The Hon Charles Morrison, MP for Devizes, the charming, second son of Lord Margadale, and, as an abiding Wet, a thorn in the side of Margaret Thatcher. He was knighted in 1988 and she became Lady Morrison They would divorce in 1999. Sir Charles died in 2005. In 2012, she took up with a friend of decades, Andrew Parker Bowles, after the death of his second wife.

In 1984, both Wards remarried; Rosalind to The Hon Charles Morrison, MP for Devizes, the charming, second son of Lord Margadale, and, as an abiding Wet, a thorn in the side of Margaret Thatcher. He was knighted in 1988 and she became Lady Morrison They would divorce in 1999. Sir Charles died in 2005. In 2012, she took up with a friend of decades, Andrew Parker Bowles, after the death of his second wife.

In 1989, ten years after Elmley’s death and the extinction of the earldom, Mona Beauchamp, died aged 94 and Rosalind unexpectedly inherited Mad. There could have been echoes of the endless Jennens court case, which touched the Lygon family, and was taken up by Dickens as ‘Jarndyce v. Jarndyce’ in Bleak House. But handing the estate to the last of the Lygons avoided all that.

On her first night as chatelaine she ascended the rock crystal staircase and touched the canvas of William Ranken’s commanding portrait of Beauchamp, “It’s okay, Grandpa, we’re back.” After half a century, Sibell and Dorothy returned to their beloved Mad. (Maimie had died in 1982) With Charles, Rosalind set about restoring the 162-room house. In cleaning the moat, she had that marble bust of her grandmother fished out of the water, placing it in the entrance hall, outside the earl’s gaze. The whitewashed image of her grandmother in the chapel was also restored. In 1993, that country house saviour, diarist, and a fellow native of Worcestershire, James Lees-Milne, visited Mad and recorded being entranced by the 47-year-old Rosalind’s pre-Raphaelite beauty.

For thirty years Rosalind Morrison played an important role in the county as generations of Lygons had before: governor of King’s School, Worcester; prison visitor; friend of Worcester Cathedral; patron and volunteer of numerous local charities and good causes. She was Deputy Lieutenant of Worcestershire from 2006, High Sheriff in 2011, and in 2016 Vice Lord Lieutenant.

In December 2012, she moved to a smaller house on the estate, handing Madresfield over to her younger daughter, Lucy, who with her husband, Jonathan Chenevix-Trench, moved in with their four children (below). The house had not had young children living in it for a century.

On Rosalind’s death, Madresfield has never looked so perfect. Some 60 rooms have been redone, hundreds of chairs (some of them embroidered by Beauchamp) and sofas resprung and recovered, panelling repaired and waxed, rooms refreshed and repainted, pictures conserved and rehung; and eighteen new bedrooms. As the visiting writer, Selina Hastings put it (and this was at the end of Mona’s almost endless tenure) there were Holbeins and Bronzinos, tapestries, cases of Limoges, enamelled snuff-boxes and diamond-framed miniatures, Buhl furniture from Versailles. There are even curtains, still hanging, that had been stitched by Queen Anne and her favourite, Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough.

Rosalind Morrison is survived by her two daughters and grandchildren, signalling the thirtieth generation to live at Madresfield, where the sundial in the garden reads, “That day is wasted on which we have not laughed.”

Sign In

Sign In 0 Items (

0 Items ( Search

Search

Thanks, Mark. I always look forward to your articles on the rich (and ex-rich) and famous.

A good read. That’s amazing (among other things) about Beauchamp befriending and funding Henry Lawson. How did that happen – did he just walk out of Government House and call in at the pub where Lawson was drinking? Or did he invite Lawson to a soiree with the footmen serving?

I know it is being corrected but in the interim, Rosalind Lygon did not remarry her first husband, Gerald Ward but the Hon Charles Morrison MP for Devizes (later Sir Charles Morrison)

Interesting to see art drawing so much on life, as of course it always does. And what lives these were, these privileged people in their enviable circumstances as they move in and out of one of England’s Great Catholic Houses. Thanks for this splendid in all ways biographical account of one family’s eccentricities and duties done, and of the heritage that was part of their very being, all laid out for us as a genealogical memento mori following the demise of one of its scions. A very enjoyable read which for me was a much needed and pleasant distraction from today’s various political woes.

And as for the ‘shut the door’ mishearing, I am bound on reading that to recount here that old saw retold in working class households of the Duchess letting off one of those subtle but pungent stink bombs some ladies do make, and who, in an attempt to deflect responsibility, sternly says to the Butler:

Johnson, stop that.

Certainly Your Grace, replies the suave Johnson, smoothly enquiring: Which way did it go?

Boom tish!